Placeless Places

The Death and Rebirth of Third Spaces

Placeless Places The Death and Rebirth of Third Spaces

Date Summer 2022

in preperation for undergraduate thesis, watch proposal video

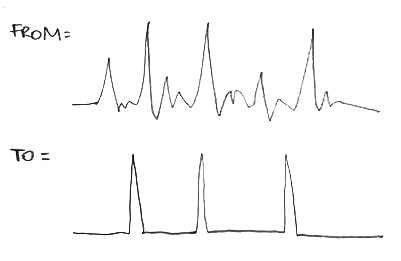

The European Commission’s Atlas of the Human Planet finds that 85% of the world is urban and 2.87 billion people across the globe have smartphones – lifelines that only require electrical infrastructure to maintain, which is more readily available than affordable housing. At the dawn of the metropolis, Simmel writes that the urban environment is so overstimulated that we ought to have psychological barriers to protect ourselves from the inundation of information. Technology has not only become a distraction from the cacophonic urban experience, but it has also distilled our passage through the city down to efficient and direct jumps between specific destinations, thereby allowing us to self-isolate in anti-urban bubbles that block out the entanglement of circulations and circumstances essential to public life.

1. Places

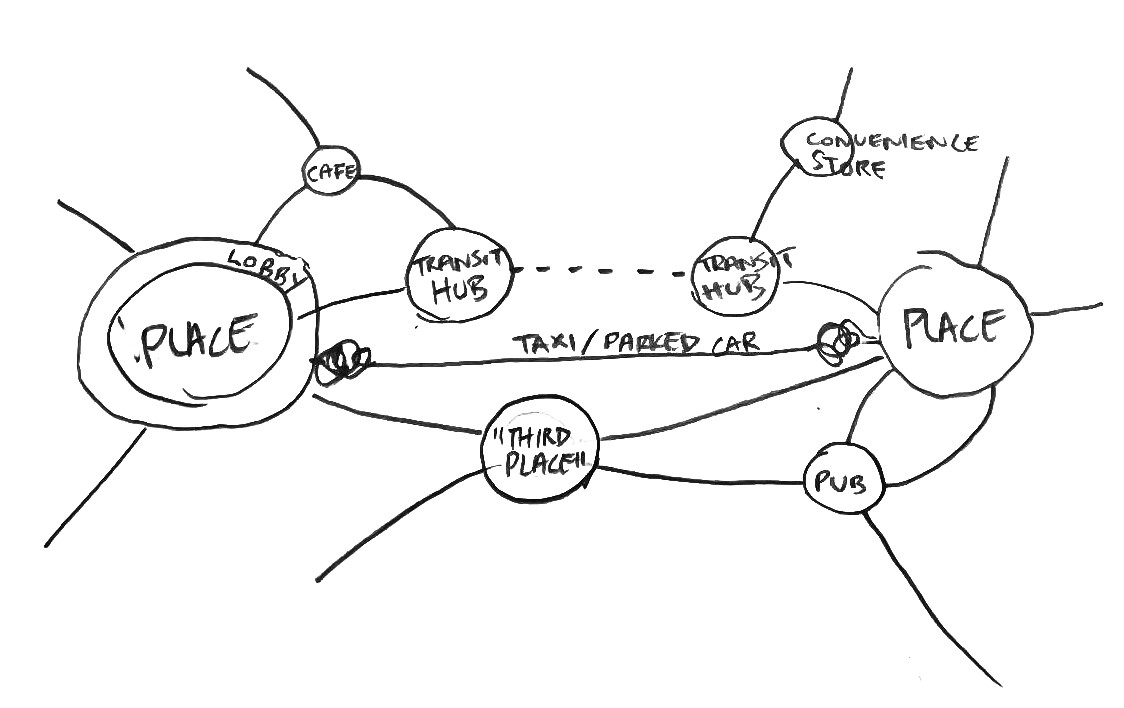

Oldenburg’s The Great Good Place writes that if ‘the first place’ is the home, the second being work (or any space of production), then ‘third spaces’ would be “neutral grounds” that allow people to be sociable “when they have some protection from each other”1 – a home away from home. These are the not-truly-public public spaces that both accommodate democratic discourse and the conjuring of collective imaginaries for the future, whilst also being moments of escape/pause/informality from the continuous flow of traffic, information, and material. They were the Greek agoras, the 18th Century French salons, the English coffeehouse/pubs, the 20th Century American malls; and are now the queues at every Starbucks2, the awkward loitering in lobbies and train stations, the typical hair salon where everyone engages in the same activity independently/intimately, thereby providing the “leveler” for casual conversation3. Our city used to be a rich littoral landscape of things and places within a sea of third spaces floating around, so what happened?

¹ Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place, (Da Capo Press, 1989), 22.

² Ginia Bellafante, What We Lose by Hiring Someone to Pick Up Our Avocados for Us, (New York Times, Jan 31, 2020)

³ Oldenburg, The Great Good Place, 26.

Oldenburg’s The Great Good Place writes that if ‘the first place’ is the home, the second being work (or any space of production), then ‘third spaces’ would be “neutral grounds” that allow people to be sociable “when they have some protection from each other”1 – a home away from home. These are the not-truly-public public spaces that both accommodate democratic discourse and the conjuring of collective imaginaries for the future, whilst also being moments of escape/pause/informality from the continuous flow of traffic, information, and material. They were the Greek agoras, the 18th Century French salons, the English coffeehouse/pubs, the 20th Century American malls; and are now the queues at every Starbucks2, the awkward loitering in lobbies and train stations, the typical hair salon where everyone engages in the same activity independently/intimately, thereby providing the “leveler” for casual conversation3. Our city used to be a rich littoral landscape of things and places within a sea of third spaces floating around, so what happened?

¹ Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place, (Da Capo Press, 1989), 22.

² Ginia Bellafante, What We Lose by Hiring Someone to Pick Up Our Avocados for Us, (New York Times, Jan 31, 2020)

³ Oldenburg, The Great Good Place, 26.

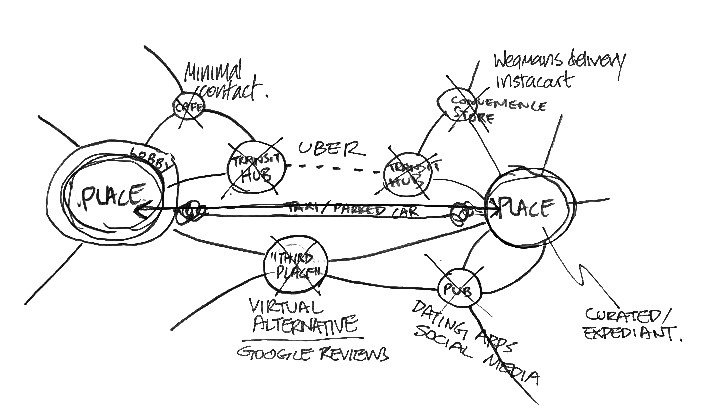

2. Grindr, Uber, Virtual Church: The Emergence of Placeless-ness

“While electricity concentrates, electronics disperse.”4 The internet has sorted us into interest groups that mirror ourselves, resulting in a public realm that is similarly self-absorbed. Digital alternatives of third places resulted in the mass migration away from the physical realm. It has also given peripheral communities the ability to practice multicultural politics of difference (Charles Taylor), previously unattainable in a liberal democracy that values individual dignity and localism. Architect Andres Jaque attributes the demise of the gay nightclub to Grindr and what he calls Grindr Urbanism5, which allows men to meet in private rather than public places. It is increasingly atypical for these intimate chance encounters to occur in digital spaces, where we enjoy a newfound sense of anonymity and expressiveness. We loiter on Twitter or Reddit to shout out our opinions when we are too shy to do so in person on a plaza. COVID-19 has further perpetuated the erasure of third spaces as churches, office socials, meetings, classrooms, galleries become virtual. We have come to realize that physical space can be non-essential for certain human interactions. A swath of the population might even find that immobility has liberated us from the limitations of time and space: a business executive can now hold multiple Zoom meetings across different time zones without even leaving their front door – a practical and financial upheaval of how cities operate as entanglements of infrastructure, mobility, and relationships begin to untether.

The rise of commodifiable personal mobility and delivery services also negate our need to be on the street, in so eliminating the chance encounters or collective loitering that can only be found in third places. The comfort of being alone in an Uber replaces the claustrophobic experience of sharing the same square foot with five other people on the rush hour train, as well as the 15-minute walk from the train station to the office under uncomfortable weather. You can now have someone do your groceries via an app and have it sent to your apartment instead of taking half an afternoon out to do it yourself and risk exchanging awkward pleasantries when running into a casual acquaintance.

Technology has also eliminated waiting. Why need a lobby or waiting area when an SMS can let you know when to leave your car and be seated? There are rarely queues at Starbucks nowadays since everyone pre-orders on the app and picks up their drink at a counter. Even when someone is in line, they are probably conference calling into their AirPods without ever making eye contact with the worker taking their order6. The contemporary city is a landscape of unsaturated, untextured, homogenous placeless-ness where we don’t go to places and things; things and places come to us.

⁴ Mark C. Taylor, Any Magazine (1994)

⁵ Cynthia Davidson, Connected Apart, featured in Expansions: Responses to How Will We Live Together?, Edited by Hashim Sarkis and Ala Tannir, (La Biennale di Venezia, May 2021), 149.

⁶ Bellafante, What We Lose by Hiring Someone to Pick Up Our Avocados for Us.

“While electricity concentrates, electronics disperse.”4 The internet has sorted us into interest groups that mirror ourselves, resulting in a public realm that is similarly self-absorbed. Digital alternatives of third places resulted in the mass migration away from the physical realm. It has also given peripheral communities the ability to practice multicultural politics of difference (Charles Taylor), previously unattainable in a liberal democracy that values individual dignity and localism. Architect Andres Jaque attributes the demise of the gay nightclub to Grindr and what he calls Grindr Urbanism5, which allows men to meet in private rather than public places. It is increasingly atypical for these intimate chance encounters to occur in digital spaces, where we enjoy a newfound sense of anonymity and expressiveness. We loiter on Twitter or Reddit to shout out our opinions when we are too shy to do so in person on a plaza. COVID-19 has further perpetuated the erasure of third spaces as churches, office socials, meetings, classrooms, galleries become virtual. We have come to realize that physical space can be non-essential for certain human interactions. A swath of the population might even find that immobility has liberated us from the limitations of time and space: a business executive can now hold multiple Zoom meetings across different time zones without even leaving their front door – a practical and financial upheaval of how cities operate as entanglements of infrastructure, mobility, and relationships begin to untether.

The rise of commodifiable personal mobility and delivery services also negate our need to be on the street, in so eliminating the chance encounters or collective loitering that can only be found in third places. The comfort of being alone in an Uber replaces the claustrophobic experience of sharing the same square foot with five other people on the rush hour train, as well as the 15-minute walk from the train station to the office under uncomfortable weather. You can now have someone do your groceries via an app and have it sent to your apartment instead of taking half an afternoon out to do it yourself and risk exchanging awkward pleasantries when running into a casual acquaintance.

Technology has also eliminated waiting. Why need a lobby or waiting area when an SMS can let you know when to leave your car and be seated? There are rarely queues at Starbucks nowadays since everyone pre-orders on the app and picks up their drink at a counter. Even when someone is in line, they are probably conference calling into their AirPods without ever making eye contact with the worker taking their order6. The contemporary city is a landscape of unsaturated, untextured, homogenous placeless-ness where we don’t go to places and things; things and places come to us.

⁴ Mark C. Taylor, Any Magazine (1994)

⁵ Cynthia Davidson, Connected Apart, featured in Expansions: Responses to How Will We Live Together?, Edited by Hashim Sarkis and Ala Tannir, (La Biennale di Venezia, May 2021), 149.

⁶ Bellafante, What We Lose by Hiring Someone to Pick Up Our Avocados for Us.

3. Google Reviews and the Natural History Museum

Even when we do go out, technology ensures that we don’t waste any time getting lost by making passive decisions for us. Much like the Natural History Museum that “inquires into what we see, how we see, and what remains excluded from our seeing”7, our reviews and comments on the internet edit and mediate the framed spectacles and viral experiences that are recommended to everyone else. There is now an ‘institutionally’ legitimized guided tour in where to go and how to get there, which is further codified by tourism, imaging, branding, and the profiting of the Western ruling class – capitalists. We no longer need to look up towards the streetscape so long as we keep looking down at our phones and the head towards the direction Google Maps tells us to go in. We no longer need third places to provide urban sanctuaries from overstimulation when we trust in technology to be our psychological defense and liaison, connecting us with the right people to unlock the appropriate doors.

⁷ “Mission Statement”, The Natural History Museum.

Even when we do go out, technology ensures that we don’t waste any time getting lost by making passive decisions for us. Much like the Natural History Museum that “inquires into what we see, how we see, and what remains excluded from our seeing”7, our reviews and comments on the internet edit and mediate the framed spectacles and viral experiences that are recommended to everyone else. There is now an ‘institutionally’ legitimized guided tour in where to go and how to get there, which is further codified by tourism, imaging, branding, and the profiting of the Western ruling class – capitalists. We no longer need to look up towards the streetscape so long as we keep looking down at our phones and the head towards the direction Google Maps tells us to go in. We no longer need third places to provide urban sanctuaries from overstimulation when we trust in technology to be our psychological defense and liaison, connecting us with the right people to unlock the appropriate doors.

⁷ “Mission Statement”, The Natural History Museum.

4. Third Spaces

“Contemporary public life might better be understood as a kind of discursive cigarette – without smoke or nicotine, but with plenty of metaphorical fire – over which one can linger while sharing the exotic air of so much new and intense urban life.”8 With the physical disappearance of generic yet familiar third places, we are at risk of losing the interactions that protect us from becoming addicted to isolation. That said, living online does not eliminate or undermine the need for physical space, it may in fact inform what new third spaces should accommodate. The emergence of PC bars, e-sports arenas, VR infrastructure… all signal new opportunities for congestions/pauses/collectivities that can be designed.

⁸ Sarah Whiting, Linger, For a Moment, In the City, featured in Expansions: Responses to How Will We Live Together?, Edited by Hashim Sarkis and Ala Tannir, (La Biennale di Venezia, May 2021), 40.

“Contemporary public life might better be understood as a kind of discursive cigarette – without smoke or nicotine, but with plenty of metaphorical fire – over which one can linger while sharing the exotic air of so much new and intense urban life.”8 With the physical disappearance of generic yet familiar third places, we are at risk of losing the interactions that protect us from becoming addicted to isolation. That said, living online does not eliminate or undermine the need for physical space, it may in fact inform what new third spaces should accommodate. The emergence of PC bars, e-sports arenas, VR infrastructure… all signal new opportunities for congestions/pauses/collectivities that can be designed.

⁸ Sarah Whiting, Linger, For a Moment, In the City, featured in Expansions: Responses to How Will We Live Together?, Edited by Hashim Sarkis and Ala Tannir, (La Biennale di Venezia, May 2021), 40.

© 2023 Tsz Man Nicholas Chung / all rights reserved