From Utopia to Ubiquity

Moving Walkways at Expo ‘70

From Utopia to Ubiquity Moving Walkways at Expo ‘70

Date Spring 2024-2025

Location Osaka, Japan

Advisors Seng Kuan, Roi Salgueiro Barrio, Abby Spinak

Special thanks to Michelle L Hauk and Ines Zalduendo for your advisement, Kenzo Tange Archive (Harvard GSD), National Diet Library, Expo ‘70 Commemorative Park.

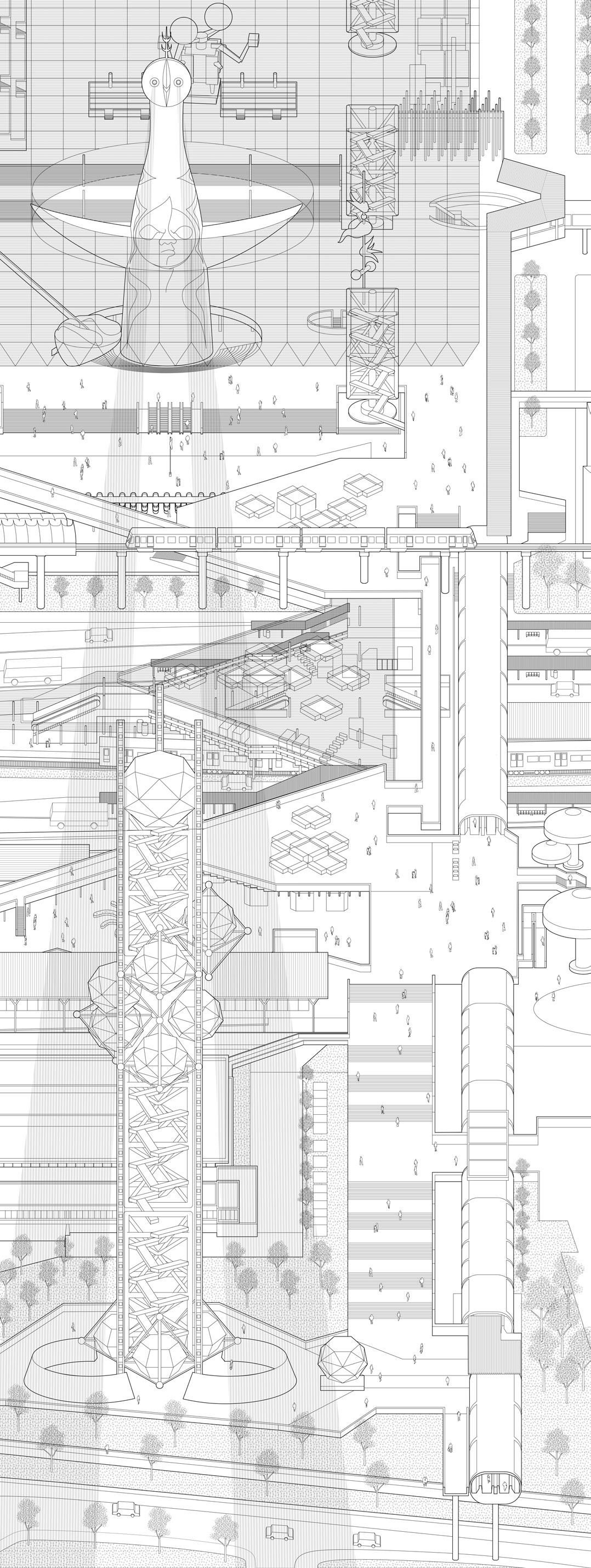

The 1970 Osaka Exposition (Expo ’70 hereinafter) was a menagerie of architectural spectacles – from inflatable and tensegrity structures to the capsules and megastructures that purported to territorialize vast landscapes. Technocentric utopianism ideologically underpinned the design of Expo ’70, and although many of the pavilions warrant standalone explications of how they reflects the new materiality and high-tech obsession of the 1960s, the architecture that best inflects the aesthetics, techniques, and imagination of this historical moment is arguably the moving walkways that connected the pavilions. It may seem surprising given how ubiquitous they are in today’s urban fabric, but moving walkways or people movers were relatively obscure infrastructural novelties up until the mid-1960s. The masterplan of Expo ’70 was the first instance where it was practically deployed as a completely independent circulation system for a ‘city’, the subject of intense speculation by the Metabolism movement in architecture. This paper will trace the assimilation of Metabolism’s utopian fantasies into the everyday fabric of Japanese cities through the microhistory of Expo ‘70’s moving walkways – contoured from both the disciplinary history of modern architecture as well as the global circulation of technologies that were essential in their material and cultural assemblage.

Concurrent to the large infrastructural projects that were realized in the early 1960s, speculative proposals were made by both bureaucrats and designers that reimagined the image of Japanese cities as they continued to grow. The most significant contribution in this body of work was Tange’s Plan for Tokyo, 1960, which had an axial megastructure spanning across Tokyo Bay made of a series of linked highways. Civic programs were centralized along the trunk and floating residential units branched out perpendicularly to form an open-ended system that challenged “prewar notions of suburbanization, which [Tange] described as a closed system.” Analogous to how cells metabolize in a biological organism, cities can hypothetically expand and contract perpetually under a per-established structure. As evidenced by the innumerable studies and sketches from Tange’s project notebook, there was a clear preoccupation with finding the appropriate forms and scales for urbanization as it accelerated exponentially. Networks of traffic and movement were stacked on top of each other, and much consideration was put into the sectional interweaving between different layers. Tange’s proposal became the foundation of the Metabolism movement, an offshoot of Modernism that prioritized technocentric planning and urban growth.

![Detailed photograph of Tokyo Plan, 1960 model. Tange, Kenzō (1913-2005). The Kenzo Tange Archive, Gift of Takako Tange, 2011. Tokyo Bay Model=東京湾の 模型, 1960. Courtesy of the Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design.]()

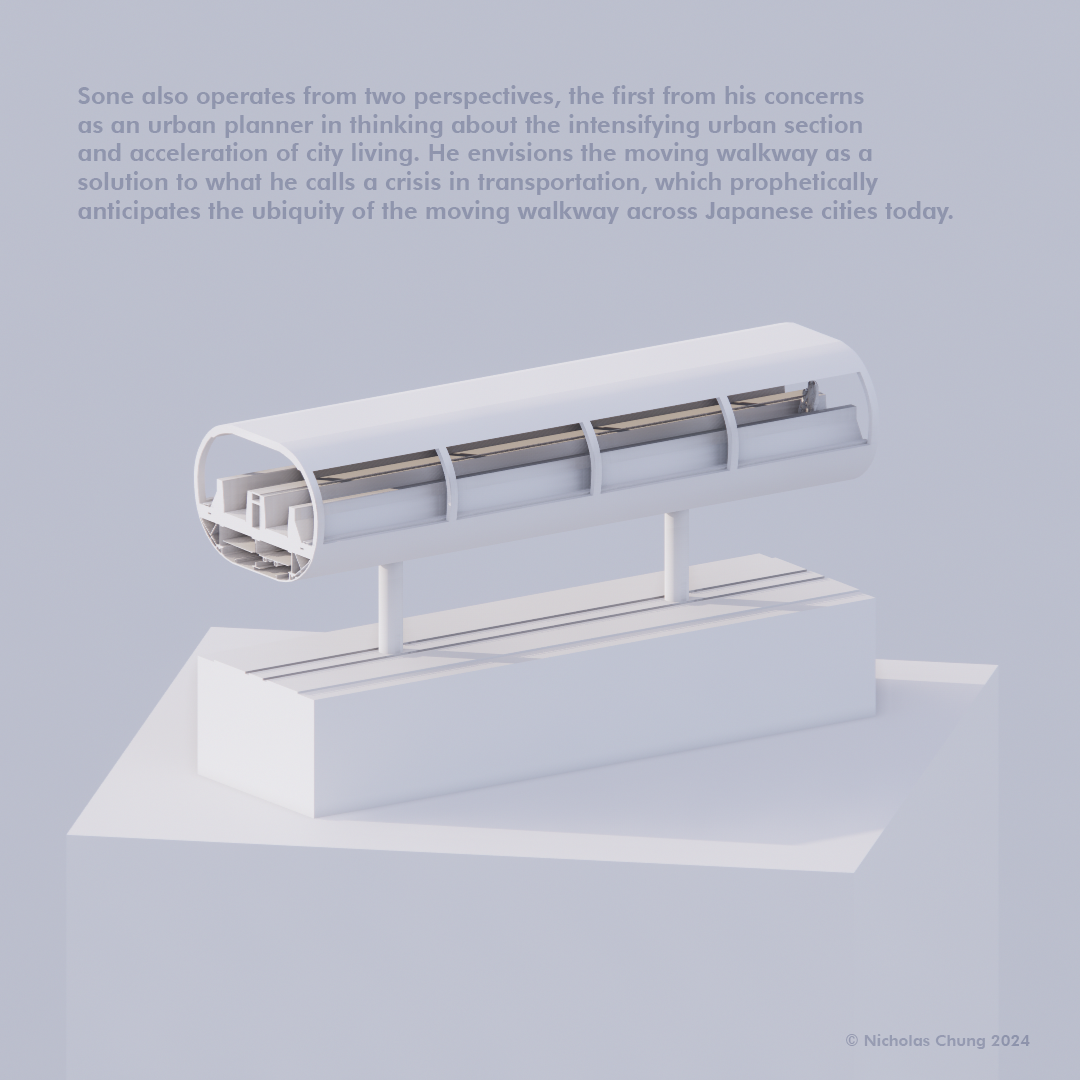

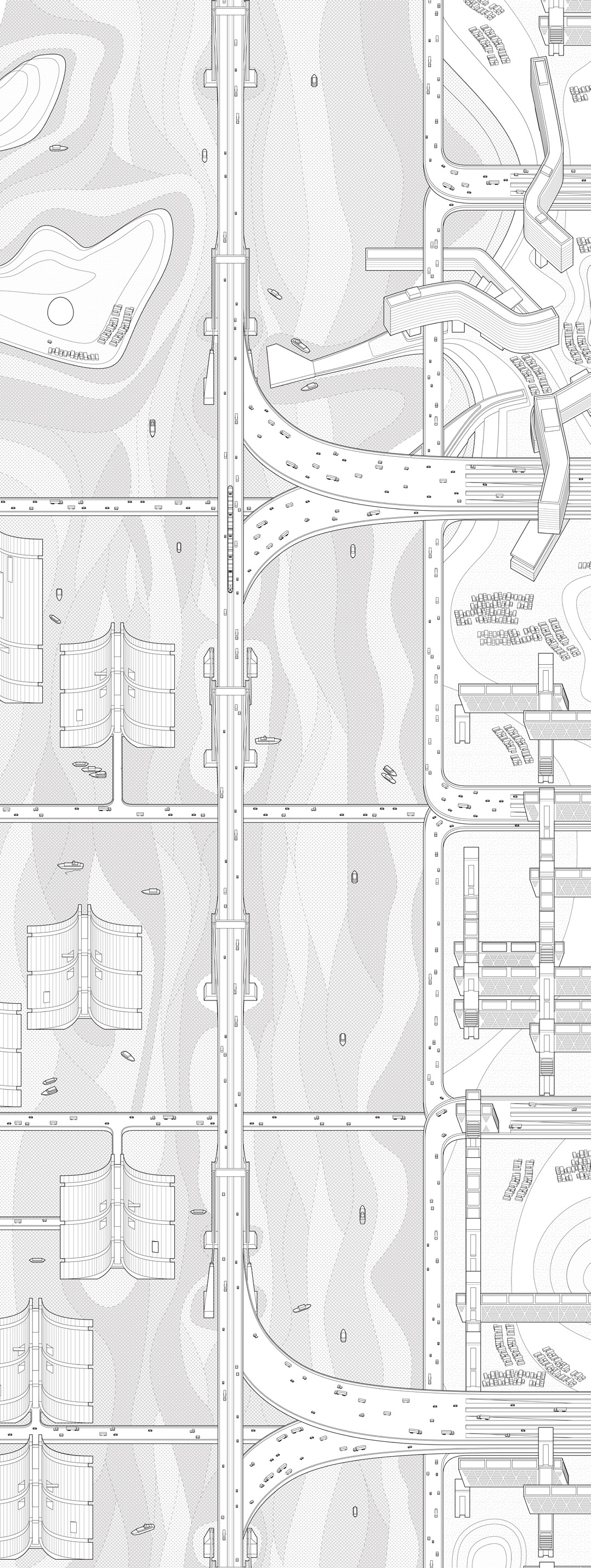

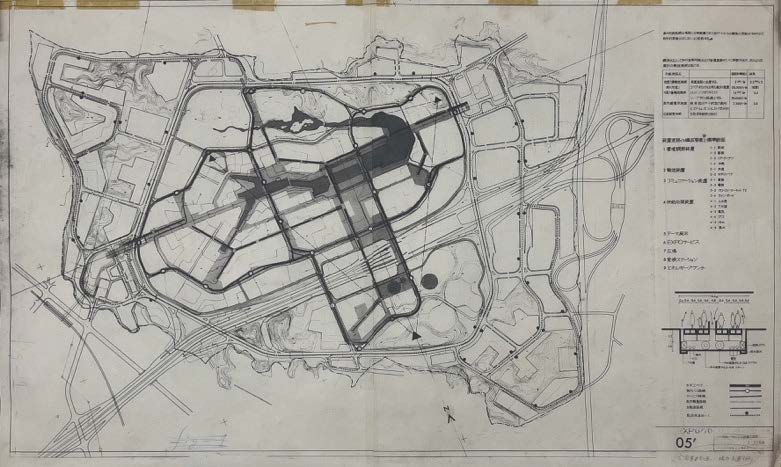

In the second draft of the 1967 infrastructure proposal, Tange and the Site Planning Committee introduced plans for a low-speed mass-transit system named the ‘apparatus street’11 (裝置道路 = sōchi dōro). These walkways integrated HVAC, energy, and communication systems sectionally, forming a centralized armature for both human and mechanical circulation. The proposal suggested that four branches would break off from the Festival Plaza, connecting an estimated 429,000 daily visitors between the North, East, and West sub-gates. At the end of each branch, along the perimeter of the expo site, would be entry pavilions with programs such as information centers, restrooms, and food courts. These nodes would also connect the city’s transportation network as well as other modes of traversing within the expo site, including a high-altitude viewing ropeway, low-speed taxis for sightseeing on designated pedestrian paths, a high-speed monorail, and service roads for maintenance and emergency vehicles. A ‘walking belt’ (ウォーキングベルト) would be installed on this elevated walkway and its entire length would be covered with a roof to protect it from the sun whilst still providing views of the exterior.

![Road networks of Expo ‘70. Tange, Kenzō (1913-2005). The Kenzo Tange Archive, Gift of Takako Tange, 2011. Osaka Expo=日本万国博覧会大阪万博, 1966 – 1972. Courtesy of the Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design.]()

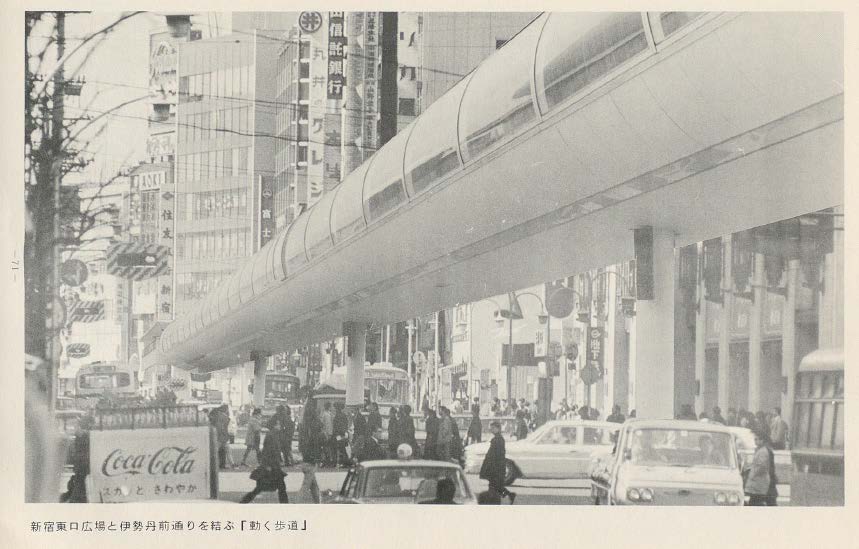

The moving walkway was an opportunity to reframe future infrastructure as a practical problematic of urban planning, rather than a symbolic gesturing of utopia or cynical criticism. Sone’s interest in embedded systems within the urban section was explicated in an essay he co-wrote with Sei Oyuki and Yuji Morioka for JA’s special issue on Expo ’70. He remarked that an increased demand for speed and smooth communication without collisions required the development of a mass transit system with a strong public orientation. He posited that the slow uptake of this effort constituted transportation crisis and saw Expo ’70 as an analogous networked city where the density of the Festival Plaza also required safe and comfortable decongestion through new transportation infrastructure. A month before Expo ‘70’s opening, Sone led a sub-committee at the Transport Economics Research Center and published a report that proposed various scenarios in which the moving walkways he helped design could be integrated into various urban scenarios. A major objective discussed was the consolidation of existing transportation networks in a manner that would be administratively feasible. The report included visualizations for two hypothetical projects in Tokyo: one in Ginza and the other in Shinjuku. The first applied example for Ginza was to link three disconnected subway lines running in parallel through a perpendicular corridor. Commuters would directly traverse between platforms via moving walkways underground without needing to exit and re-enter at different levels. The report suggested that this strategy would increase the overall walkability of the busy district without compromising the capacity of vehicular traffic. The second example for Shinjuku’s Fukutoshin Line proposed inserting elevated moving walkways as an independent network above ground. Unlike the Ginza scheme, this was a direct transplant of the walkways from Expo ’70 as evidenced by how the renderings collaged views from inside the recently completed walkway tubes with views of Shinjuku to simulate a visually stimulating liminal experience. The report suggested that by isolating the walkways as an architectural object, commuters could perceive the city’s spatial logic. Although the Shinjuku scheme was never realized, Ginza Station, as it is today, is an underground street that closely mirrors this report’s recommendations. Sone’s walkway network and the discourse he produced around it implied that the integration of technology, which is not the same as technocratically-driven architecture, was changing the relationship between cybernetics, communications, and how people experience city living.

![Proposal for Shinjuku Fukutoshin, from “Research report on the suitability of moving walkways for urban transportation,” Transport Economics Research Materials (Tokyo: Transport Economics Research Center, March 1970), 67-73. Courtesy of National Diet Library.]()

© 2023 Tsz Man Nicholas Chung / all rights reserved