Memo 019

The Mythology of A Japan:

Roland Barthes’s Empire of Signs

Nicholas Chung, 12 December 2024

Preface: This is not a book review; but rather an essay that imitates a book.

Imagine

This attempt to dissect Roland Barthes’s convoluted The Empire of Signs will begin as all beginnings should: by analyzing the beginning.

“If I were to imagine a fictive nation, I can give it an invented name, treat it declaratively as a novelistic object, create a new Garabagne, so as to compromise no real country by my fantasy (though it is then that fantasy itself I compromise by the signs of literature). I can also – though in no way claiming to represent or to analyze reality itself (those being the major gestures of Western discourse) – isolate somewhere in the world (faraway) a certain number of features (a term employed in linguistics), and out of these features deliberately form a system. It is this system which I shall call: Japan.”[1]

Barthes’s opening gambit is a disclaimer of fiction, albeit much more self-indulgent than the ones that typically precede a television show today, which under no uncertain terms sets up the nature of his book: an imagined depiction of a reality that bears some semblance to the one which the reader finds themselves in. Any identification with persons, places, and objects is intentionally coincidental and should not be inferred as an accurate portrayal of reality. The book, The Empire of Signs, fashions itself as an improvement on Henri Michaux's Voyage en Grande Garabagne, where Michaux explores the tension between real and imagined journeys. But where Michaux destabilizes the narrative hierarchy of signifying systems by confusing the fabulation of signified constructs and actual referents, Barthes embraces the traveler’s naivety to create a Japan that is reconstructed through his imagination. There are no referents, only signifiers and the fact that they signify some “faraway” cultural contexts inaccessible to him.

As ‘the soul does not think without phantasm’[2] and thought (text) needs an image to give it corporeality, to imagine is to mediate perception and understanding. Whereas to imagine a fiction, as Barthes does, is to connect observation with a fabricated explanation. The following essay will explore the various facets of the semiotic system that Barthes constructs whilst he is internalizing his encounter with the real Japan vis-à-vis his culturally limiting syntax stemming from Western epistome (more specifically, French literary semiotics discourse). It should be heavily prefaced that Barthes himself has only interfaced with the real Japan through secondary sources.

“The author has never, in any sense, photographed Japan. Rather, he has done the opposite: Japan has starred him with any number of “flashes”; or, better still, Japan has afforded him a situation of writing.”[3]

In this one sentence, Barthes estranges his authorial subjectivity through the third person. “The author” too is an autonomous object that is adequate to the object called “Japan”, i.e. the subject that Barthes draws inspiration from. His pairing of “faraway” with calligraphy of the kanji character “無” (mu, translated as emptiness)[4] reflects the factual emptiness that is behind all of the signs that he shall present. The book is not about introducing the reader to Japan, given the fact that ‘Japan’ or ‘Japanese’ is in neither the book’s title nor any of the chapter titles. Barthes’s invented Japan has an inherently compromised internal logic, as such his opening disclaimer stresses his entfremdungseffekt (alienation) with the subject matter and disillusions his readers (presumably also foreigners at the time of publication) of any notion that the real Japan will be rendered intelligible or familiar for them.

The “faraway” will remain an isolated black box, and the phenomenon that is called “Japan” is merely, to use a Lacanian framework, the screen on which Barthes projects a desire for semiotic autonomy against modern positivism. What the objects signify does not matter, what matters is that they signify. The Empire of Signs is therefore best approached as a thought exercise in which Barthes rehearses the semiotic method in search of jouissance through meaning.

Semiotic System and Semiotic Objects

Through the fictive journey that Barthes goes on and his encounter with the various semiotic objects of his constructed empire, he claims the emergence of a semiotic system. However, if the objects he presents have no fidelity in their representation, it might be more appropriate to suggest that he is constructing an ecology or ecosystem of signs as he goes along. Barthes would like his worldview to be a closed system, one that allows his signifiers to simply just be interreferential – to not require justification through a second-degree referent.

In Saussurain linguistics, the signifier is the readily available language that Barthes expands to include the non-linguistical. The signified is the wider concept it refers to, and the referent (irrelevant here) could be characterized as the concept’s anchorage in reality. Barthes comes from literary criticism, but this book begins to engage with the other disciplines of semiotics, such as sociology, psychoanalysis, political theory, and philosophy. Additionally, though The Empire of Signs is not a major character in Barthes’s extensive oeuvre, it does showcase an intuitive interplay of arbitrary, diacritical, and synchronic analyses. Arbitrary analysis posits no inherent relations between objects, and can be understood as a system that is consequent of social conventions. For example, the act of bowing as a greeting and the sound-act of “itadakimasu!” to give thanks before a meal have no specific correlation with one another, aside from the fact that they are both norms embedded in the ritualist performance of everyday life. Diacritical analysis is the comparative study of two objects through difference and negation, or to put it simply: something has meaning only when it is understood in relation to something else in its series. The most common analogy would be phonetics and the variations of letters, words, and speech, such as the usage of ‘é’ versus ‘ë’. Synchronic analysis privileges pure analysis over diachronic experience, meaning it is ahistorical and one can engage the material purely on the basis of the context in which is presented, to make-do with the as-found. One can make an observation about an object and interpret its method of signification through deductive reasoning, then arrive at a conclusion about its inscribed surface without needing to look into its deep structure.

Barthes is most comfortable with the final modality as it authorizes an interreferential system of signs, meaning that the analysis of the various signifiers will make legible an independent feedback loop that is not forcibly inscribed by the author. As conceptually appealing as it may be, the number of alterations required to force the emergence of an ecosystem renders the effort of reading instead of fabulating moot. Therefore, it might be inevitable that Barthes needed to invent his own ecology of semiotic objects to make possible his utopian, autonomous semiotic system – which, by the very definition of ‘utopia’, is unattainable.

Inventing, then Interpreting Japan-esque

The semiotic objects Barthes employs are, in order of appearance, as follows:

Faraway (Fictive Japan as a semiotic system)

The Unknown Language (A culturally inaccessible subject)

Without Words (Social cues)

Water and Flake (Food as written language)

Chopsticks (A tool to deconstruct linguistic food)

Food Decentered (Part as whole)

The Interstice (The process is more important than the container-name)

Pachinko (Intensive labor, performed)

Center-City, Empty Center (Tokyo)

No Address (Lack of specificity and hierarchy, privilege dérive)

The Station (A pragmatic monument without monumentality)

Packages (Empty containers as mobile signs)

The Three Writings (Theater: Dissimulation)

Animate/Inanimate (Theater: no soul, just motion)

Inside/Outside (Theater: no strings, no destiny)

Bowing (A meaningless gesture from convention)

The Breach of Meaning (Haiku: straightforward representation)

Exemption from Meaning (Haiku: aspiration for linguistic flatness)

The Incident (The mirror does not reflect the self, but reflects emptiness)

So (Resisting definition and commentary)

Stationary Store (Calligraphy breaks the sign)

The Written Face (Transvestite performers emulate feminine signs only)

Millions of Bodies (Individuality is not closure, but difference)

The Eyelid (The ‘Japanese’ face is all surface, no depth)

The Writing of Violence (Violence through the Western gaze is artistic)

The Cabinet of Signs (Art can be isolated from an inaccessible culture)

*In parentheses is this reader’s understanding of each chapter as a key phrase.

Over the course of 110 pages, Barthes presents 26 short essays, each being a narrow ontological study of a language system, behaviour, phenomenon, the body, organization, or objects of artistic value. Though some are clearer than others, the chapters produce groupings that are divided into themes, disciplines, or modes of analysis. Without Wordsand Bowing reveal the lack of substance behind protocols of politeness, whereas the sociological mass spectacle in the Pachinko is culturally reflected in The Three Writings corporeally – all of which point to an arbitrary understanding that the externality of the body-container is irrespective of individual consciousness. The Interstice would addendum that the Millions of Bodies in their mechanical processes of moving through the world are collectively autonomous and are isolated from notions of agency – an almost Heideggerian abstraction of the body down to only social conventions as a common denominator.

Where conventional structuralism would use a semiotic relation to point to an external referent, Barthes invents his own set of meanings that work towards the negation of his system as a whole. Each chapter presents an object as an inscribed black-box that interrelates to other chapters, and within each object is a set of self-referencing signs that produces an entropic feedback loop that inevitably un-reifies the object itself. This is exemplified in Barthes’s description of the Japanese stationary store.[5] Yet the chapter really is not about the store itself, but rather the instruments of its commerce: the pen (brush) and the paper. Barthes infers that “it is in the stationery store that the hand encounters the instrument and the substance of the stroke, the trace, the line, the graphism; it is in the stationary store that the commerce of the sign begins, even before it is written.”[6] It is not really about the store or the apparatus, it is the interface of mind, body, and surface through the mechanical act of signification that interests him, much like his analysis of the body and theatre prior.

“The object of the Japanese stationary store is that ideographic writing which to our eyes seems to derive from painting, whereas quite simply it is painting’s inspiration.”[7]

Barthes is interested in a type of signifier that the stationary store readily affords – Japanese calligraphy, which, unlike Anglo-Saxon scripts, are self-contained characters that, through its construction or assemblage of various parts becomes a graphical image tied to an idea. Yet since the character is drawn alla prima, which means that the mechanical act has already been rehearsed in the mind before being performed in actuality, Barthes would argue that premeditation makes the ideograph singular and flat as one cannot delaminate the character to find indexes of repetition and erasure. The ideograph is totally flat and self-enclosed, and much like haiku poetry, what one sees is what one gets. If the theatre and mass spectacle suggest the isolation between thought and action, the “pre-editing”[8] of Japanese writing brings forth the idea that action can be separated into first, its contemplation in the mind, and then secondly, its bodily execution without meaning.

Barthes would also intensify the potency of his Japanese ideograph through a recursive comparison to the American and French stationary stores – and their affordances.

“That of the United States is abundant, precise, ingenious; it is an emporium for architects, for students, whose commerce must foresee the most relaxed posture […] a good domination of the utensil, but no hallucination of the stroke, of the tool…” whereas “The French stationary store […] remains a papeterie of bookkeepers, of scribes, of commerce; its exemplary product is the minute, the juridical and calligraphed duplicate, its patrons are the eternal copyists…”[9]

Yet the problem is not whether it is good or bad that the Western stationary store has become too populist or too elitist, but it is the fact that they became non-generic – a subset propriety of the wilful author – that Barthes is critiquing. The Japanese stationary store is a site of soon-to-materialize signs that are floating around in collective consciousness, whereas the Western stationary store is merely a facilitator of individual desire. The Western author constructs a narrative through the linear combination of the alphabet, whereas the Japanese ideograph already pre-exists, and the artist is merely materializing it onto paper via a pre-determined mechanical gesture. Though Barthes does not pick up on this nuance, the notion of writing with a specific stroke order and how the stroke flares or rounds in ideographic calligraphy also play into this supposition. It is through such differences that this reader concludes that Barthes is attempting to reveal an aesthetic proposition or sensibility that is ‘Japan-esque’. It is not authentically Japanese, nor is it ‘Japan-ish’, for it does not aspire to be accurate but is instead already a precise approximation that is, as the opening chapter makes clear, fully dissimulated.

This ‘Japan-esque’ proposition would require not only the passive interpretability of signifiers but also a convincing framework in which they can mobilize as hyper-signs. Writing was therefore a very astute medium for Barthes for the conventional chaining of characters into a sentence would break the graphical insularity of each word. The final sentence of this chapter teases this possibility:

“[…] a true graphical art which would no longer be the aesthetic labour of the solitary letter but the abolition of the sign, fling aslant, freehand, in all the directions of the page.”[10]

It is easy to discount the “abolition of the sign” as one of Barthes’s many unresolved aporias throughout the book, but this does not need-be if “abolition”, or the formal conclusion of perceiving signs as static objects to be analysed, is not understood as the loss of independent meaning but instead an expansion of scope to consider how the series-image is acting on the world. Textuality is not the consideration of atomized particulates, but patterning that produces logic as a wider mental image, which cares little about where it begins and ends, but rather how it serially reproduces itself as a mechanical process. The pattern on a kimono is not dissimilar to the plan of “No Stop City” that Archizoom produced on a typewriter.

![No-Stop City by Archizoom[11]](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/ad0cd74faa84646ef72a1171a3bb38cf37a6659334b9476ab1c3f08e8fc2ac9b/superstudio.jpg)

![Piece of cloth for kimono with round fan patterning[12]](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/10f2fd685492635a3c88c9badd0dea94506d334e003057e1bb257ebe0e3f8c9a/kimono.jpg)

Mobilizing the Semiotic System

If one were to reorganize the seemingly sporadic list of objects into a pattern, a feedback loop that diagrammatically entails some determinacy, then the entire semiotic system becomes legible through scalar causality, elaboration, and diagnosis. The first component, scalar causality, posits a perpetuation between the body’s surface and the environmental surface. The Package, for example, is both a description of the inability to decipher what is beyond the external surface, which doubles as a shorthand for how the Japanese body contains double narratives – the image of the self that is always presented and the true self that is not made visible for interpretation.

“[…] the package is not empty, but emptied: to find the object which is in the package or the signified which is in the sign is to discard it: what the Japanese carry, with a formicant energy, are actually empty signs.”[13]

The Japanese veneer is unapologetically plastic and disposable – one changes their official stance reflexively in accordance with the spontaneous changes of one’s contingent environment. Barthes notes that this necessity to augment the self-image is not an internal proposition, but rather a consequence of the absence of specificity in the urban environment. He remarks that the city has no addresses that provide more than postal knowledge, which is only accessible to and useful for bureaucratic administration.

“[…] you must orient yourself in it not by book, by address, but by walking, by sight, by habit, by experience; here every discovery is intense and fragile, it can be repeated or recovered only by memory of the tract it has left in you.”[14]

One becomes a local by walking the city repeatedly, to assimilate into an indigenous knowledge that then gives access to the know-how of anonymity and convention. Behavioral cues, like bowing, become mechanical instinct as the body is conditioned to respond to certain protocols. This is reflected into the morphology of the city, as in Barthes’s perception, Tokyo is a city with an empty center. Though he has correctly identified that the heart of Tokyo, which is occupied by the imperial palace, is an urban void, his inaccessibility to, or refusal to engage with, the history of urbanism during the feudal period renders impossible a more sophisticated reading about the high city, low city, and ring roads that organize what he has abstracted into an ideogram hierarchically. Instead, the reader is left with a rather unsatisfying simplification of the city as sporadic fragments around “an empty subject”[15]. Nonetheless, Barthes is content with this artifice for it validates his elaboration on the body. The empty center diverts all value judgment to the membrane, which is exemplified in the textuality of both human and non-human agents.

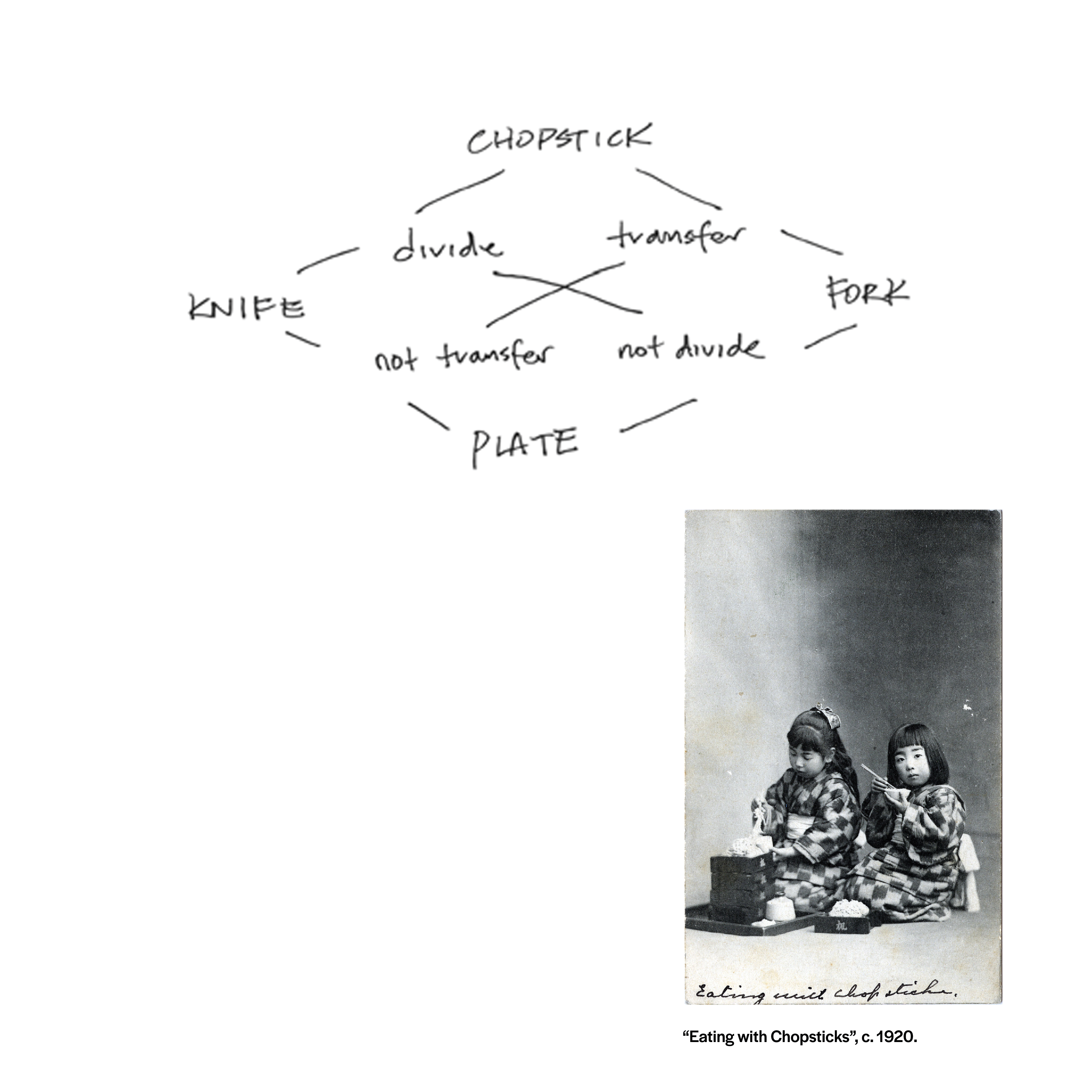

In culinary practice, Barthes identifies the delicate compartmentalization of the dinner tray, where the dish is not a “reified product”[16], but rather a refined elaboration of its preparatory process. Through the deconstruction of a singular object into its base elements, the Japanese context ascribes a foreign meaning to reductive subjects that subvert the French gaze. Barthes remarks that “in France, a clear soup is a poor soup; but here the lightness of the bouillon […] gives the idea of a clear density, of a nutrivity without grease, of an elixir all the more comforting in that it is pure.”[17] In a non-hierarchical framework that is signified by the dinner tray with each part being its own constituent whole. The planimetric arrangement produces diacritical relations that, in Barthes’s interpretation, are also non-hierarchical. Like the city, the small plates and trays are empty centers that are interstitially mediated by the bodily appendage – the chopstick. As an apparatus, it breaks down both the material and symbolic singularities (color, delicacy, touch, effect, harmony, relish”[18]) with decisive agency. “They never violate the foodstuff: either they gradually unravel it or else prod it into separate pieces, thereby rediscovering the natural fissures of the substance. Finally and this is perhaps their loveliest function, the chopsticks transfer the food” in a way that semiotically negates both the fork and the knife.

Precisely Inaccurate: The Mythology of A Japan

In the absence of a stable referent (the real Japan), and Barthes’s own desire for semiotic autonomy, the book is intersticed with several chapters on Japanese culture, or the invention of such supposition, to diagnose some notion of reciprocity between a fabulated sensibility (Japan-esque) and the processes of signification (Barthes’s fictive Japan). This diagnosis is demonstrated by an aesthetic preference for flatness as cultural technique. In The Written Face, Barthes heavily implicates the theatricality of positing one’s image through the transvestite performer, for in his Japan, the portrayal of characters in the dramatic arts is not tied to the gender identification of its actor. The role is therefore a skin, or a bodysuit of signs, that the (male) actor inhabits. Barthes would argue that the overaccentuated makeup on actors is an assemblage of feminine signs, while the actor himself does not aspire to become feminine internally. Identity as information is laminated onto epidermal presentation, and as a communicative surface, it is always overtly straightforward as to redirect any interest toward what lies beneath.

Barthes’s diagnosis is an elaboration of how he sets up The Three Writings to point towards a cultural predilection for process over result, and he suggests a straightforwardness through the idea of ‘flatness’ found in haiku. In four successive chapters, he performs a literary analysis of poetry that resolves itself through the following sequence of claims: Firstly, haiku delivery is direct, the imagined and the symbolic are compressed into the image, and what one sees is what one gets. Secondly, that this directness reflects an aspiration for ‘linguistic flatness’, which is decentered and regionally idiosyncratic as a whole object. Thirdly, this flatness as a reflective surface reifies not the self, but rather nothingness. Finally, this empty center, or lack of symbolic meaning, makes the subject of study difficult to define or critique. For Barthes, these attributes sufficiently constitute a milieu to diagnose the exigence of his menagerie of signifiers, and he falls back onto them when precisely executing his semiotic readings of various objects. The relationship between signifier, signified, and the context of their emergence are now assembled and diagrammatically his semiotic system becomes a self-reifying pattern, something that is predictable and scalable.

If Barthes’s earlier opus Mythologies is a compilation of short object-oriented ontologies of why red wine at the dinner table or the way indicators blink a certain way on a Citroen is quintessentially French, then this lesser-loved sibling is a series of mini-object-lessons of what makes something ‘Japanese’, or more accurately, Japan-esque. As Barthes prefaces, this book is not intended as an accurate depiction of reality, and The Empire of Signs is often misunderstood because of Barthes’s liberties in constructing his fictive nation, which his readers might not fully appreciate. The haikus that Barthes presents are originally written and formatted in Japanese, which are then translated to French when Barthes is interpreting them, and then translated to English for their publication. By the time the reader is encountering the supposed original text, it has already been translated, and possibly reformatted numerous times. For poetry, especially literature of Sinophonic origin, the cadence, rhymes, line construction and other elements are all composed in a very specific manner that might not be conducive for Western translation. Therefore the ‘Japan’ Barthes presents through cultural technique is only a Japan that happens to share the name of the real one. When considered that way, it is no wonder that the semiotic analysis precisely and conveniently arrives at the same incorrect diagnosis, because, unlike his study on France, this ‘Japan’ is truly a pure mythology of his imagination.

The Book as a Semiotic Object

However, if one were to look at the broader picture, figuratively and literally, and revisit the table of contents as scalar elaborations versus diagnosis, what becomes evident is the book’s composition as two parts, and the rhythmic interplay between observation and explanation. The objects are also grouped somewhat thematically, moving from language frameworks, to apparatus, to the environment, then art and literature, which is reflected back onto the body, and closes by validating his own hypothetical method. It reveals not only a rhythm but a narrative line that is not initially apparent to the reader, rendering the book itself as an object with its own autonomy, not unlike the semiotic objects it contains. If one were to take Barthes’s observation of Japan’s semiotic objects being emptied containers, and that only the inscribed exterior surface is of interest, then one can even take the radical step of ignoring the written content in its entirety and assume the object-ness of the book itself must intrinsically demonstrate the techniques of signification and interpretation.

The first twelve chapters from Faraway to Packages ontologically present objects that reflect social organization patterns in a way that is self-evident. This first half demonstrates a possible scalar and medium reciprocity, with acute tangents that present cultural or philosophical assumptions for their exigence. The final fourteen chapters from The Three Writings to The Cabinet of Signs interchange between tangible and intangible linearly, whereas the first half operates more as a feedback loop with elaborations on specific items. The second half of Barthes’s presentation requires conjunctive leaps in reasoning, for he is attempting to proclaim a hierarchical logic system that is first ideological, then material. This forms the basis of his diagnosis of the first twelve chapters. The reader should be recursively reflecting back on their initial encounters with faraway Japan as they come to grasp with Barthes’s methodology in reading graphical signifiers by moving forward in the book. This reading of images is indexed through the small annotations that Barthes places beneath each image, which is a way of conditioning the reader to think about how they should look or read the graphical signs in the same manner as Barthes. They come across as if they were the spontaneous notes that Barthes would have made as he was walking down the streets of Tokyo. It brings the author and his readers into the same moment, where they are both active participants in this thought experiment. This intention is best exemplified by the first and final images of this book, which are on the second and second to last page of the book. Both are images of the actor Kazuo Funaki, presumably taken in rapid succession of one another. Besides the change from a stoic expression in the first image to a wry, half-smile in the final image, they are almost completely identical. What is interesting though, is that the first image is centered on the page and is not given an annotation anywhere on the spread. Yet the final image is not only off-centered, but it also is given the caption “close to smiling”[19]. In both chapters, Barthes does not discuss Funaki nor does he contextualize the images. Yet the addition of a caption would suggest that by progressing through the book, both Barthes and the reader are now finally able to interpret the image semiotically, where it was still an enigma upon first encounter. This mirroring encloses the book systematically, as a pattern, and in an almost Shakespearian way, is Barthes rehearsing Prospero’s concluding monologue in the Tempest. The actors, as foretold, melt away as Barthes’s fictive Japan closes on itself the same way it began. The completed pattern is now self-perpetuating and can now reproduce itself as the readers reflect on their own situated contexts.

This dissection of The Empire of Signs as a semiotic object will end the same way this essay began: by analyzing the beginning – or what comes before the beginning. The book is dedicated to Maurice Pinguet, a contemporary of Barthes and Michel Foucault who was the academic authority on Japanese culture and civilization in France. The publication of Pinguet’s seminal work on voluntary death in the Japanese context would have coincided with The Empire of Signs, which invariably calls attention to the discursive discrepancies between the steadfast accuracy of Pinguet and the precisely inaccurate approach of Barthes. To this reader, this dedication seems to be Barthes’s admittance of his inability, and therefore reluctance, to present the real Japan as it was, whilst providing his colleague as an alternative to readers who are seeking cultural legibility instead of speculation.

This is followed by the table of contents and list of illustrations. Graphically, the two lists syntactically mirror each other, with the former in bold majuscule script aligned to the center and the latter in lower case justified to the left. The page numbers also mirror each other, which suggests that there is no hierarchy between content and illustration, and that they are comparable in the semiotic method.

“The text does not “gloss” the images, which do not “illustrate” the text. For me, each has been no more than the onset of a kind of visual uncertainty, analogous perhaps to that loss of meaning Zen calls a satori. Text and image, interlacing, seek to ensure the circulation and exchange of these signifiers: body, face, writing; and in them to read the retreat of signs.”[20]

Barthes lays bare his thesis in the preface before the book even begins. This is why the book does not have a narrative arc that begins and ends: it is a visual, graphical, tactile object that cares more about how its surface (the page) is inscribed and interpreted. The content, textual and graphical, is merely a scalar extension or elaboration of this patterning. There is no symbolism or real meaning behind it, for like the reimagined haiku poetry contained within it, The Empire of Signsaspires for a certain semiotic flatness. What one sees is what one gets, and that in itself is meaningful enough.

notes:

[1] Barthes, Roland. Empire of Signs, translated by Richard Howard, New York: Hill and Wang, 1982, 3.

[2] Aristotle. "De Anima." In The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation, edited by Jonathan Barnes. Book III, Chapter 7.

[3] Empire of Signs, 4.

[4] Empire of Signs, 5.

[5] Empire of Signs, 85-87.

[6] Ibid, 85

[7] Ibid, 86

[8] Ibid, 87

[9] Ibid, 85

[10] Ibid, 87

[11] Branzi, Andrea. 2006. No-stop city : Archizoom Associati. Orléans: HYX.

[12] 19th century. Piece of Cloth for Kimono with Pattern of Round Fans (Uchiwa), Bamboo, and Interrupted Stripes. Piece of cloth for kimono, Textiles-Dyed. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[13] Empire of Signs, 46

[14] Ibid, 36

[15] Ibid, 32

[16] Ibid, 12

[17] Ibid, 14

[18] Ibid, 18

[19] Ibid, 108

[20] Ibid, Preface

[1] Barthes, Roland. Empire of Signs, translated by Richard Howard, New York: Hill and Wang, 1982, 3.

[2] Aristotle. "De Anima." In The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation, edited by Jonathan Barnes. Book III, Chapter 7.

[3] Empire of Signs, 4.

[4] Empire of Signs, 5.

[5] Empire of Signs, 85-87.

[6] Ibid, 85

[7] Ibid, 86

[8] Ibid, 87

[9] Ibid, 85

[10] Ibid, 87

[11] Branzi, Andrea. 2006. No-stop city : Archizoom Associati. Orléans: HYX.

[12] 19th century. Piece of Cloth for Kimono with Pattern of Round Fans (Uchiwa), Bamboo, and Interrupted Stripes. Piece of cloth for kimono, Textiles-Dyed. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[13] Empire of Signs, 46

[14] Ibid, 36

[15] Ibid, 32

[16] Ibid, 12

[17] Ibid, 14

[18] Ibid, 18

[19] Ibid, 108

[20] Ibid, Preface