Memo 018

Japanese Mass Housing and its Multiple Natures

Nicholas Chung, 22 August 2024

One of director Hideaki Anno’s preferred mise-en-scène tropes for establishing a mood of melancholy and disenchantment is the depiction of barren parks and plazas situated amidst dilapidated danchi apartments. These spaces convey a bleakness that aestheticizes the dissolution of Japan’s middle-class dream, coinciding with the closure of the Economic Miracle. In a context that values newness, these apartment complexes and new towns became cultural symbols of outdatedness.

The origin of this cultural imagination can be traced back to as early as 1958 in director Keisuke Kinoshita’s film, The Eternal Rainbow, where workers' apartments were described as ‘beautiful,’ and the promise of an idyllic lifestyle seemed inevitable as the camera panned across a totalized landscape of danchi apartments rising in rapid succession. However, less attention is given to the parks and green spaces filling the interstitial areas, where one catches glimpses of planters, saplings, and playground furniture sprinkled with children.

In 2013, director Yoshihiro Nakamura’s See You Tomorrow, Everyone more explicitly depicted life in a danchi complex through a melancholic lens that echoes the characters’ entrapment and exasperation within an ossified socioeconomic stratum. The film avoids the rose-tinted lens of nostalgia, opting instead for an exploration of indeterminacy and anxiety looming over the constructed social life of the danchi, much of which was built in the urban landscapes between apartments.[1] It is noteworthy that there is limited discourse around the design and production of these landscapes, though unsurprising, given that the latter half of the twentieth century in Japanese architectural discourse was dominated by the revolution of domestic interiors and urban sprawl that occurred as rapidly as Japan’s economy skyrocketed.

Danchi (団地) translates directly to 'group land' and refers to apartment towers popularized in the 1960s and 70s to meet a rising demand for housing. Initially emerging on the outskirts of cities as small complexes, they later expanded into suburbs as New Towns (ニュータウン). The urban landscape design in danchi housing represents a novel practice that neither projects an aesthetic philosophy rooted in Japanese tradition nor reproduces the international styles influencing Japan in the 1950s and 60s. Instead, it could be characterized as the fragmentation and compartmentalization of landscape design into a binary of large-scale ecological remediation and achieving economies of scale through standardization. This marked a clear departure from traditional landscape design conventions that involve various disparate disciplines like zoen (造園) or fukei (風景), all of which share an underlying philosophical sensibility – oku (奧). In "City with a Hidden Past," Fumihiko Maki describes a conceptual centripetal inwardness that organizes space-making in Japan. Influenced by geomancy, nature is perceived as part of the built world, engaging it relationally rather than adhering to a picturesque or sublime Western sense.

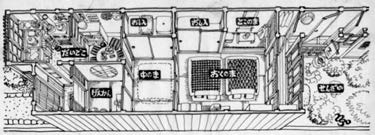

Maki notes that "the Japanese have long seen small spaces as autonomous microcosms and thus developed the perception that a part was in fact also a whole."[2] This sensibility has given rise to typologies such as bonkei, bonsai, and the tsubo-niwa, where all rooms face inwards into a small landscape courtyard. These courtyards are arranged to evoke an artistic impression of nature, signifying a cosmic totality that infuses the house with energy. Merchant townhouses called machiya, typical during the Heian and pre-war era, exemplify how the Japanese retained a traditional conception of domesticity and nature as the nation urbanized during the early modern period. This emphasis on the interiority of nature will be uprooted during the post-war era as dwellings continue to move upwards away from the ground plane.

Origins: Entering the 1960s

After the Second World War, Japan was thrust into a period of rapid reconstruction. In 1950, Kenzo Tange's Hiroshima Peace Memorial introduced Modernism to Japan, becoming the default modus operandi for national reconstruction. Tange's Tokyo Bay plan further solidified Japan's alignment with Modernists, influenced by his tenure at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and his involvement with the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM). It was during this global exchange that Tange likely encountered designs for "towers in the park", the Radiant City, and case studies like the Hatfield New Town Act of 1946. This cultural exchange would have also reinforced ideas like the Garden Cities by Ebenezer Howard and Charles Purdom that was introduced in 1907[3] in conjunction with Clarence Perry’s Neighborhood Unit. Japan’s exposure to and idealization of Western Modernity gave rise to what Sujin Eom and Aihwa Ong refer to as "crippled" or "incomplete modernity,"[4] introducing an anxiety that persisted. This phenomenon perpetuated developmentalism in Japan, leading to a population influx and rapid urbanization during the 1950s and 60s.

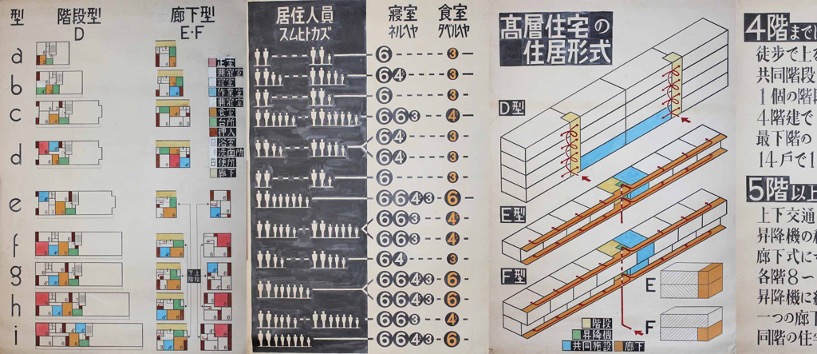

Tokyo's population surged from 11,275,000 in 1950 to 16,679,000 in 1960, while Osaka's rose from 7,005,000 to 10,615,000, marking the era now known as the Japanese Economic Miracle. The peak of this transformation occurred in 1955 when the Nendo Keizai Hakusho (Annual Economic White Paper) declared that "Japan was no longer post-war; economic recovery had been accomplished, and it was time for the nation to set its sights on modernization."[5] The rise of a middle class with increased consumer power fuelled a newfound desire for homeownership. The Japanese Housing Corporation (JHC) was established as a state-sponsored agency tasked with constructing mass housing complexes serving as transitional settlements for the middle class before moving into suburban houses. Nishiyama Uzo documented this transition from low-rise detached homes to apartment towers with DK or LDK units. His anthropological drawings highlight the disappearance of private gardens in favour of higher density and compactness.[6] In the 1960s, danchicomplexes extended to the suburbs, marking the popularization of new towns just outside metropolitan areas. The imagery of these domestic interiors often features a backdrop of a mediated exterior, where the aesthetics of 'wildness' is relegated beyond the complex boundaries. The liminal spaces between apartment towers are sparsely landscaped with a few trees and mass-produced furniture. The landscape of New Towns bears semantic resemblance to the towers in the garden, yet they do not fulfill the socioecological functions of the Garden Cities they seek to emulate. Clearly departing from traditional schemas, this new practice of urban landscape design in emergent suburban areas can be characterized as follows:

1. The separation of nature (ecology) and urban landscape (economies of scale).

2. Domestic landscapes moved from internal to external, spatial to image.

3. The first generation of New Towns was unable to resolve its problem of incompatibility.

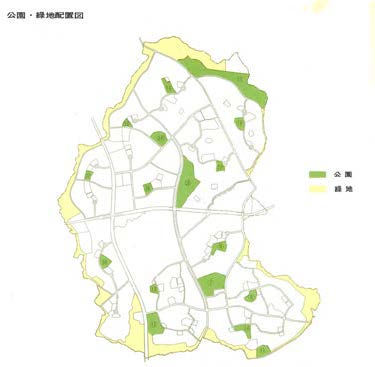

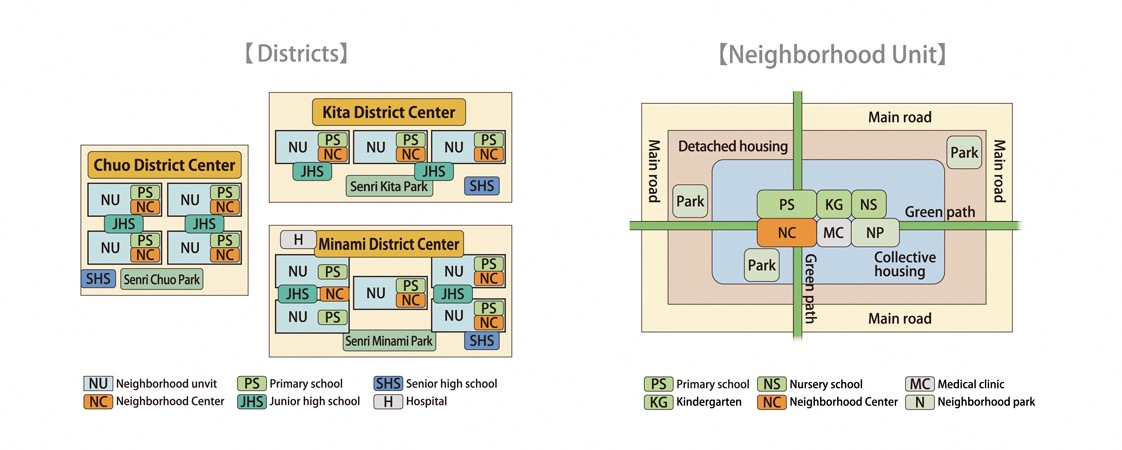

Senri New Town (NT), Japan’s first new town outside metropolitan Osaka, opened in 1962 and has 1,160 hectares and 21% of the land is devoted to 17 parks and a green belt that encloses the territory.[7] The aim of the green belt is to preserve some of the hilly landscape that was flattened during the construction of Senri NT. Some of the original bamboo forests and red pine forests were passed down and replanted along the periphery of Senri. Though this green belt does serve to remediate some ecological damages caused by the tabula rasa of the existing Senri Hills, its main function was to control the rate of urban sprawl. This practice of segmenting out territory away from development as a means of controlling growth was also adopted in subsequent New Towns such as Tama NT. However, it should be noted that for the majority, these areas of ecological protection are on the periphery of settlements and do not engage in the everyday life of the danchi. The popularization of high-rise dwellings also resulted in a detachment of domestic life from the ground plane, which in traditional townhouses produced a direct linkage to nature via the courtyard garden. Activities that used to take place in private open spaces within a house are now pushed out onto balconies or the streetscape. Nature in dwellings that used to be spatial became graphical – a view outside the window and an amenity that is part of an increasingly commodifiable lifestyle. This psychological transition from uchi to soto (inside to outside), produced an absence of domestic oku which the JHC addressed through its large-scale urban planning.

Senri NT was divided into 3 districts, which were subdivided into 12 neighborhood units which could be recognized by the prefix Shinsenri- and the suffixes -dai or -machi. Each unit of roughly 60 to 100 hectare has a core comprised of schools, clinics, a neighborhood center, and a park, with each district also having a regional park. Since the New Town was private-public joint venture, the JHC enforced the Land Readjustment Law that provisions a certain percentage of developable land per plot for public facilities and infrastructure.[8] This produced a cluster schema that parallels the neighborhood unit system of Clarence Perry and pursues the aspirations of the Garden City, as evidenced by early proposals by various urban design labs that were working in tandem with the JHC and municipality.

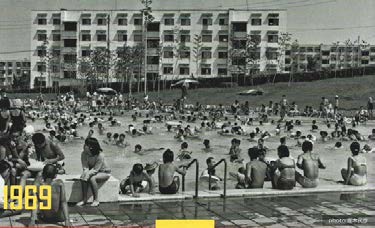

The parks of Senri are urban voids between buildings that leverage the existing hilly topography with Radburn’s layout of cul-de-sacs. Yet the practice of landscaping in these parks and recreation areas mobilizes an imported conception of nature that privileges activating the civic sphere through commodities and amenities, which was achieved by populating the public spaces which were “strikingly of large scale and magnified”[9] with mass-produced elements such as planters or furniture. This tendency was perpetuated by “signs that local governments are not in favor of the development of housing sites because the expenses required for the development of public services and utility facilities, such as roads, public parks, sewage systems and schools”[10] would have been significant. As such, the JHC had to practice by treating landscape design not as the consolidation of ecological systems, but as investing in public utilities that have monetary value in order to cover the costs of providing “better environments for a satisfactory cooperative living.”[11] This new type of recreation space is exemplified by Yamatodani Park, which was both a conventional park and a swimming pool, technically had all the elements of Japanese sansui (山水) (water, mountain/hill, vegetation), but supplants the sensibility of a pure, cosmic totality by allowing its transgression, occupation, and commodification en masse.

Residents of JHC housing also had to pay a public utility fee to supplement the costs of maintaining and managing the disparate departments of water management, sewage disposal, and sanitizing public spaces.[12] This decoupling of the various functions of landscape design is partly a result of the JHC’s fragmented business structure. The three lines of business are construction, management, and development, and within them, responsibility for the various components of the parks is compartmentalized into “service facilities”, “public facilities”, and “facilities for the redevelopment of [the] local environment.”[13] As such, landscape practice in danchi projects tended to be either macro-scale infrastructural systems like water treatment ponds that would require larger proportions of funding[14] or micro-scale interventions using ready-made elements like follies or furniture. This is exemplified in the design of children playgrounds that directly transplanted typologies and standardized configurations from pre-existing case studies, a method that was preferred for streamlined the construction process and minimized unit cost for manufacturing.[15] This scalar extreme of only macro and micro landscape design, paired with the exclusion of natural ecology to the peripheral green belt, culminate into the resultant aesthetic of follies in the absence of a landscape.

Contemporary Practice: 2000 and Onwards

The 1970s and 80s witnessed the ongoing surge of New Towns alongside transit-oriented development and multi-functional cities. However, by the 1990s, this momentum came to a halt with the conclusion of the Economic Miracle and an aging population. The developmentalism that fueled Japan’s middle-class dream encountered disenchantment in what is now known as ‘The Lost Decade’. As the 21st Century unfolded, Japan faced a slow recovery from the 2008 global financial crisis, population degrowth in 2010, and the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake, displacing a significant portion of the Northeast. In 2004, the Japan Housing Corporation (JHC) merged with various government agencies, such as the Japan Regional Development Corporation, forming a new semi-privatized administrative body called the Urban Renaissance Agency (UR). This merger, in many ways, allowed for the consolidation of the previously disparate functions of landscape design within danchi projects. UR was tasked with managing Japan’s maturing housing stock and infrastructure against a stagnating civic body while responding to the various socioeconomic crises mentioned. The following case studies will showcase the contemporary and projective practices within UR that aim to:

- Remediate nature (ecology) and urban landscape design (economy) as a single practice.

- Anticipate crises.

- Diversify the social and ecological functions of landscapes within existing danchi.

Hibarigaoka-Danchi, one of the early Tokyo danchi complexes built in 1959, was retrofitted by UR in 2005 to include a biotope system to restore biodiversity within the complex’s water system. The pond utilizes well water recycled from rainwater and processed grey water from the apartments. The biotope connects existing habitats outside the danchi, forming a larger migratory network for local species. Decks extending from the informal pathway surrounding the embankment encourage local children to engage with and learn about the biotopes. Most of UR’s efforts focused on restoring ecological balance within older housing stock through small projects like Hibarigaoka-Danchi or Rebensu Garden in Yamazaki.[16]

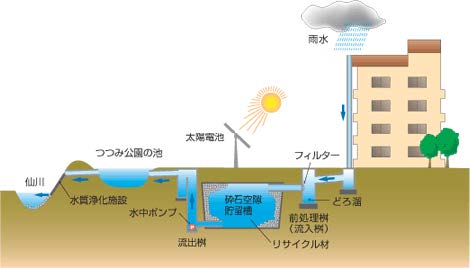

A larger intervention is the Sanvalier Sakura Zutsumi Complex (サンヴァリエ桜堤) in Tokyo, built by UR between 1999-2005. The area is renowned for its streets lined with cherry blossoms and a pre-existing hydrological system. Sengawa Mizube Park, situated in the middle of the complex, uses rainwater to supply the pond and the adjoining Sengawa River. The river underwent multiple modifications since the 1960s, including a seawall and three concrete walls, resulting in stagnant water flow and biodiversity loss. The pond collects rain in an underground storage tank, pumped up using photovoltaic pumps to create a new water source. At the macroscale, the reconnected hydrological system reconstructs the ecological and infrastructural functions of the landscape. At the mesoscale, the pond and park facilities form civic nodes, fostering collectivity within the neighborhood unit. At the microscale, the restored embankment promotes biodiversity through hydrological cycles of deposition and vegetation.[17]

UR is also involved in the reconstruction efforts post-disasters, such as the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake. The combination of the tsunami, earthquake, and nuclear fallout resulted in the geographical destruction of coastal cities and mass displacement in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures. In this context, UR operates as part of a larger regional apparatus in the reconstruction of land, rejuvenating communities, and constructing prevention infrastructure, which often doubles as memorial parks. The housing complexes are either low-rise apartments formally reminiscent of townhouses, as seen with the Aoi Apartments in Higashimatsushima, or Oura 2 Danchi in Yamada. These mass-produced apartments attempt to match or reproduce local architectural styles, but, like the danchi complexes and New Towns of old, they tend to follow a uniform layout and do not allow for planimetric flexibility found in traditional neighborhoods. As such, most of the sparse landscaping exists outside of the complex or in a dedicated void. Given that the priority of UR is to rapidly reconstruct housing for the displaced, similar to the 1950s and 60s, tower complexes like the Yamada Chuo Danchi in Iwate Prefecture opted to typologically reproduce the standard danchi formula, resulting in the same composition of open field conditions with sparse landscaping and furniture.

However, UR is also projecting possible innovations through innovation and re-examining how the practice of urban landscape design can play a more proactive role in diversifying its socio-ecological functions. In 2011, UR launched the Future of Housing Complex Project (団地の未来) and involved design practitioners such as Kengo Kuma and Kashiwa Saito to revitalize Yokohama’s Yokodai Danchi in 2017.[18] This endeavor was positioned as a model project for refurbishing and updating Japan’s existing housing stock, given that population degrowth implied a decrease in housing demand and allowed for reinvestment in deteriorating danchi projects. Outdated structures like fences, walls, and stairwells were removed, while the apartment facades were refurbished with new fenestration by Kengo Kuma’s firm. A new walkway connects the apartment towers, and a series of wooden pavilions, furniture, and platforms were introduced to populate the empty turfed plaza. The open landscape does not refer back to tradition nor does it try to conform to conventions of global contemporary practice. The open plaza is cued as flexible instead of indeterminate. It is semantically and stylistically referencing the empty public spaces of the danchi, but instead of negating their intrinsic values, Kuma and Saito reinvigorate the sociocultural and ecological aspirations of the JHC, embracing a certain Japan-ness that emerged from the latter half of the 20th Century.

The origins of urban landscape design for danchi mass housing projects emerged during a period of rapid growth, necessitated by crisis and reconstruction under the specter of incomplete modernity. It resulted in the fragmentation and compartmentalization of landscape design into a binary of either ecological remediation or economies of scale. This irreversible departure of the domestic landscape from an internalized whole to a disassociated image commodity perpetuated value ambiguity as the Japanese embraced a new, Western-influenced way of atomized individuality. This incompatibility results in disenchanted landscapes entangled with the entropic collapse of Japan’s middle-class dream. Remediation only begins at the turn of the millennium when various disciplines are reconsolidated as a single entity with sufficient agency. Yet, not unlike its origin, the conditions of practice of the contemporary moment are mired in a society of risk, where dilapidation meets degrowth, compounded by socioeconomic and ecological crises. It is no surprise then that the task of the current paradigm is the diversification of landscape practices’ functional responsibilities, once again necessitated by crises and the restructuring of Japanese social life.

notes:

[1] See also She and He by director Susumu Hani (1963) and Pom Poko by director Isao Takahata and Studio Ghibli (1994).

[2] Maki, Fumihiko. Wakatsuki, Yukitoshi. Ōno, Hidetoshi. Takatani, Tokihiko. Pollock, Naomi. Watanabe, Wakatsuki, Yukitoshi, et al. “Observing the City.” InCity with a Hidden Past. Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing Co., Ltd, 2018, 23.

[3] Oshima, Ken Tadashi. “Denenchōfu: Building the Garden City in Japan.” In Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 55, no. 2 (1996): 140–51.

[4] Eom, Sujin. “The Specter of Modernity: Open Ports and the Making of Chinatowns in Japan and South Korea.” In Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review , SPRING 2013, Vol. 24, No. 2 (SPRING 2013), 39-50.

[5] Neitzel, Laura L. The Life We Longed for : Danchi Housing and the Middle Class Dream in Postwar Japan. Portland, Maine: MerwinAsia, 2016, 23.

[6] Hein, Caroline. “Introduction: Nishiyama Uzo-: Leading Japanese Planner and Theorist.” In Reflections on Urban, Regional and National Space, Routledge, 2018, 15-45.

[7] Senri New Town. “Our Town.” Suita City/Toyonaka City Senri New Town Liaison Office. https://senri-nt.com/ourtown/en/

[8] Japan Housing Corporation and Its Achievements. Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1976, 35.

[9] Japan Housing Corporation and Its Achievements. Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1976, 1.

[10] Japan Housing Corporation and Its Achievements. Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1976, 35.

[11] Japan Housing Corporation and Its Achievements. Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1976, 3.

[12] Japan Housing Corporation and Its Achievements. Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1976, 45.

[13] Japan Housing Corporation and Its Achievements. Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1976, 17.

[14] History of Japan Housing Coroporation (日本住宅公団史), Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1981, 189.

[15] History of Japan Housing Coroporation (日本住宅公団史), Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1981, 192.

[16] Danchi X ECO. Urban Renaissance Agency, 2022, 4-5.

[17] Danchi X ECO. Urban Renaissance Agency, 2022, 6-7; see also 環境への取り組み事例 サンヴァリエ桜堤, Urban Renaissance Agency.

[18] The Future of Housing Complex Project. Urban Renaissance Agency. https://www.ur-net.go.jp/chintai/danchinomirai/

[1] See also She and He by director Susumu Hani (1963) and Pom Poko by director Isao Takahata and Studio Ghibli (1994).

[2] Maki, Fumihiko. Wakatsuki, Yukitoshi. Ōno, Hidetoshi. Takatani, Tokihiko. Pollock, Naomi. Watanabe, Wakatsuki, Yukitoshi, et al. “Observing the City.” InCity with a Hidden Past. Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing Co., Ltd, 2018, 23.

[3] Oshima, Ken Tadashi. “Denenchōfu: Building the Garden City in Japan.” In Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 55, no. 2 (1996): 140–51.

[4] Eom, Sujin. “The Specter of Modernity: Open Ports and the Making of Chinatowns in Japan and South Korea.” In Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review , SPRING 2013, Vol. 24, No. 2 (SPRING 2013), 39-50.

[5] Neitzel, Laura L. The Life We Longed for : Danchi Housing and the Middle Class Dream in Postwar Japan. Portland, Maine: MerwinAsia, 2016, 23.

[6] Hein, Caroline. “Introduction: Nishiyama Uzo-: Leading Japanese Planner and Theorist.” In Reflections on Urban, Regional and National Space, Routledge, 2018, 15-45.

[7] Senri New Town. “Our Town.” Suita City/Toyonaka City Senri New Town Liaison Office. https://senri-nt.com/ourtown/en/

[8] Japan Housing Corporation and Its Achievements. Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1976, 35.

[9] Japan Housing Corporation and Its Achievements. Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1976, 1.

[10] Japan Housing Corporation and Its Achievements. Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1976, 35.

[11] Japan Housing Corporation and Its Achievements. Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1976, 3.

[12] Japan Housing Corporation and Its Achievements. Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1976, 45.

[13] Japan Housing Corporation and Its Achievements. Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1976, 17.

[14] History of Japan Housing Coroporation (日本住宅公団史), Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1981, 189.

[15] History of Japan Housing Coroporation (日本住宅公団史), Tokyo: Japan Housing Corporation, 1981, 192.

[16] Danchi X ECO. Urban Renaissance Agency, 2022, 4-5.

[17] Danchi X ECO. Urban Renaissance Agency, 2022, 6-7; see also 環境への取り組み事例 サンヴァリエ桜堤, Urban Renaissance Agency.

[18] The Future of Housing Complex Project. Urban Renaissance Agency. https://www.ur-net.go.jp/chintai/danchinomirai/