Memo 017

Fieldnotes on Reflexivity:

Learning from Kabukicho

Nicholas Chung, 10 April 2024

How has the urban fabric of Kabukicho remain intact against the aggressive encroachment of large-scale developments originating from the station area in East Shinjuku? The following paper proposes that it is a combination of the conditions that allowed for the various exigences of the entertainment district as well as the resultant consensus of a shared reflexive mentality. Reflexivity, in lieu of resistance, leverages qualities of difference as indispensable assets to the larger developmentalist agenda. This mentality is reflected in the physical realm as rendered objects, surfaces, and apparatus, which in their reflexivity necessitate both particularity and its mobilization through labor processes. This is to say that the understanding of reflexivity reveals a possibility of symbiotic urban growth that ascribes positive value to difference.

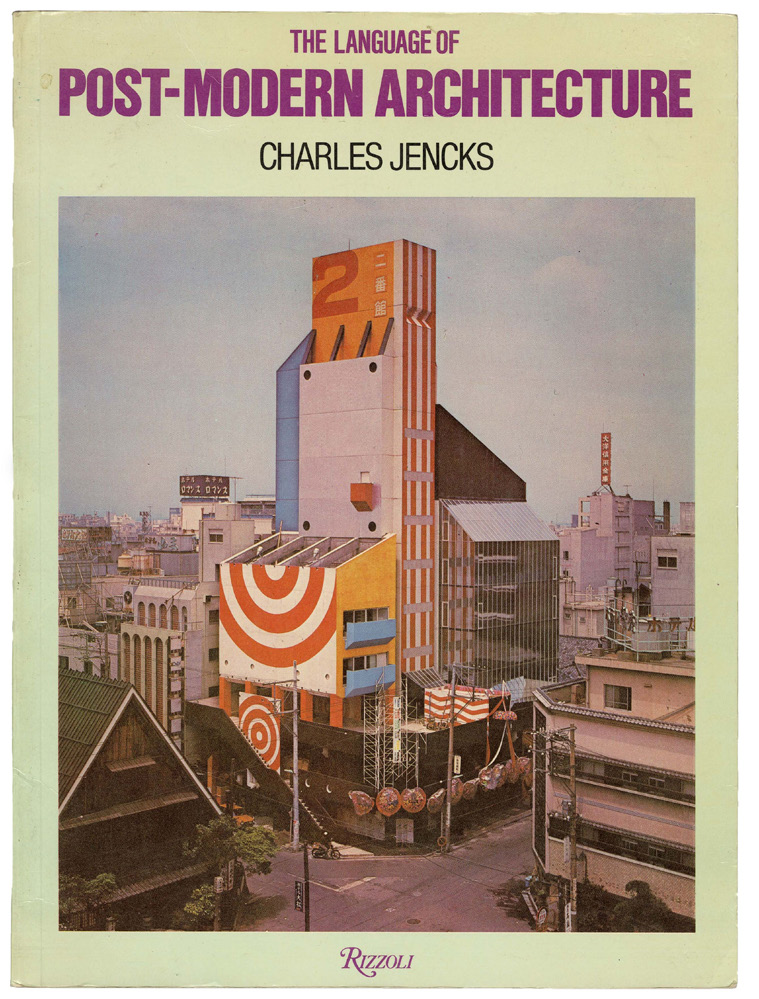

In 1977, Charles Jencks published his seminal work, The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, marking a global paradigm shift in architectural discourse. The cover for the first two editions introduced the international audience to Minoru Takeyama’s Niban-Kan (Building Number Two), sensationalizing a supposed complexity and richness that appeared to be unique to the Japanese context. This fragmented vibrancy extends to the entire Kabukicho neighborhood, which, due to its unique microhistory, stands in stark contrast to the normative, large-scale developments found in Tokyo’s urban centers, many of which are dominated by only a handful of overpowered developers.

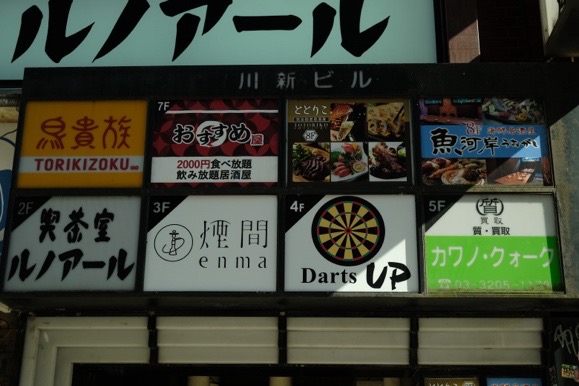

Tokyo is a city of many centers, most of which are transit hubs adjoining department stores and commercial high-rises. Density decreases, and lot sizes fragment into smaller parcels as one moves away from the station radially. Yet, to the North-East of Shinjuku Station, Kabukicho seems to have defied this formula. This is a territory that can best be characterized as where the spectacle of consumerism manifests in the transformation of signifiers into exaggerated sociocultural art. Contemporary Kabukicho is to the North of Yasukuni Avenue and is predominantly occupied by multi-story mixed-use buildings (zakkyo). Each city block is relatively fragmented, and each building tends to house four to six independent businesses. The architecture is surfaced with stretches of neon signs that are reflected and redoubled on continuous panes of glass, within which one tends to find a mix of cafes, kissas, restaurants, and izakayas. This chaotic visual front around Shinjuku Station continues perpendicularly inwards into the interior of Kabukicho and converges at the Tohoku Entertainment Building, where a life-size figure of Godzilla bears down onto the streets below. Hidden behind the large Tohoku Building are the nightclubs and bars of a similar massing arrangement as the zakkyobuildings up front – albeit instead of advertising menus and daily specials, the facades are plastered with billboards showing the monthly rankings of hosts and hostesses. Further back is the hill where Shinjuku’s infamous love hotels could be found.

This fragmented urban morphology is in stark contrast to the large-scale homogenous developments within the station area: 3-Chome, which abuts Kabukicho immediately South of Yasukuni Avenue. Aside from legacy department stores like Isetan or Lumine EST, one can also find franchise brands such as Muji, BicCamera, Uniqlo, ABC Mart… which each occupy anywhere from half to an entire city block. This zone buffers Kabukicho and the adjoining conglomerate extensions of the railway companies. The concentration and centralization of capital are also reflected in how the architecture images itself. Unlike the zakkyo buildings across the street, the surfaces on these big box stores are homogenous or singular in their graphical signification. Each building is also only occupied by one or two businesses and exudes a zen or hypermodern aesthetic. Unlike Kabukicho which addresses pragmatic entertainment needs of everyday life, the consumerist-centric urbanism of 3-Chome produces a marketable, maybe even aspirational, lifestyle.

Given that Tokyo’s other urban centers, such as Shibuya, Ikebukuro, or Ueno, tend to follow a concentric model that privileges large-scale developments close to the station, which in itself can be a mini-city with an intricate network, why has Kabukicho managed to remain a distinct identity against the aggressive encroachment of homogenizing developmentalism? A possible framework to approach this perceived aporia of scale and ownership is through a reflexive urban mentality that is a consequence of Shinjuku’s origins and contemporary social formations. "Reflexive" refers to a cognitive dexterity in the alteration of self-imaging and function to complement the changing circumstances of one’s externality. It is both a survival mechanism but also reflective of a desire against confrontational dichotomies. As such, the aporia between Kabukicho and 3-Chome does not seek to resolve itself but rather produces a symbiotic relationship between the station and its periphery by embracing difference.

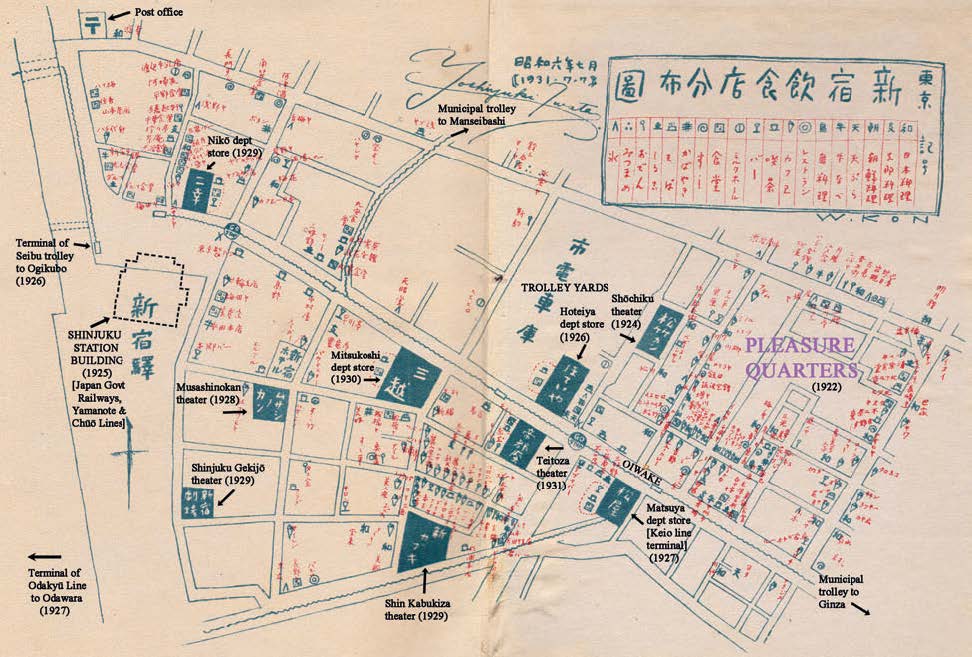

Before its current incarnation as Kabukicho, the neighborhood began as the pleasure and entertainment quarters of Shinjuku, which in the early 1700s was the gateway between Edo and Musashi Plains to the West. By the Meiji Restoration, this outpost of transient commuters was populated by unsilenced brothels, which were then set back from the main roads as the government cited them as an eyesore to modernization in 1918. The concentration of ‘inns’ was formalized as a red-light district in 1922 and continued operating as such until the banning of prostitution in 1955. Aside from the pleasure quarters, East Shinjuku was also populated by numerous eateries, shops, and department stores for the suburban middle class, typologically known as hankagai. Kon Wajiro’s survey of the area in 1931 identified three areas of interest: the South and East of Mitsukoshi Department Store, the pleasure quarters, and the “Eat-Your-Fill Alley” behind Niko department store.[1]

Five days after the end of the Second World War, the Otsu group opened the Shinjuku Black Market to the East of the station, which later expanded towards the South and West.[2] Professor Ken Tadashi Oshima remarks that as the station area remained a vital terminal for survivors of the inner city who need shelter or are transiting into the suburbs to the West, the stalls provided anything from daily necessities to illicitly acquired foreign commodities, creating a “messy urbanism” that epitomized the hankagai. In the late 1940s, there was a failed attempt to move the kabuki theater to Shinjuku, but the name Kabukicho (meaning Kabuki-District) remained. Coinciding with the Economic Miracle of the 50s and 60s was the construction of various notable architectural projects, including Takeyama’s nightclub towers: Ichban-Kan and Niban-Kan. Additionally, this period also saw the conversion of the original market stalls into bars and restaurants, along with the revival of Shinjuku’s entertainment district (sakariba) in the forms of clubs, love hotels, pleasure houses, pachinko parlors, and various other entertainment establishments that are allegedly still under the control of yakuza gangs. Though much of the original urban fabric from this period has disappeared, the composition of fragmented lots arranged in a regular layout of main roads that branch into back alleys is still visible.

Additionally, the architectural impression of the post-war era survives in yokocho like Golden Gai that were able to resist the pressures of redevelopment, though they are now distinguished by their aesthetic and temporal deviations against the homogenous city beyond it. It should also be noted that although the architectural informality of the latter half of the 20th century has largely been displaced, East Shinjuku is still the site of social lives that are othered by the dominant conservative society. For example, immediately East of 3-Chome and South of Golden Gai is 2-Chome – the hub of Tokyo’s queer subculture, with a high density of gay bars, specialty clubs, and saunas that form a tight-knit community of locals. The social production of an enclave requires both the conscious sustenance of a territory from within and the imposition of a boundary from beyond. In that sense, politics of difference in Shinjuku is not necessarily the antagonistic production of an ‘other’, but rather the sensationalizing or objectification of self to assert the enclave’s indispensability to the success of large-scale developments beyond its borders. This reflexive mentality is evidenced by how East Shinjuku evolved and repositioned itself through history, but always in the service of supplementing the needs of the transit hub or amplifying its social functions. Difference, therefore, is an artificially sustained phenomenon that diversifies what would have been a monotonous spatial narrative without harbouring resistance against the dominant agenda – which in today’s Shinjuku is the intensification of consumerist experiences.

This agenda permeates across all scales of Shinjuku’s urban existence and is heavily influenced by the area’s largest stakeholder – the train station, or more specifically, the timetable tied to the station’s corporeality that prescribes routine events requiring different configurations in the physical realm. The main variables that trigger these reconfigurations are population density and the speed of circulation, both of which are tied to the station and triggered by the predictable – often overlapping – timetables of office workers, tourists, nightlife denizens, and service workers that keep the whole infrastructural systems running. Each rush hour introduces a gallery of rogue elements that disrupt the presiding cast of characters who are performing a specific spatial narrative. In the quiet hours of dusk, the streets are lined with cargo trucks and trolleys moving boxes of produce and products; the morning rush hour brings in office workers, followed by tourists as the department stores and shopping districts open for business; from 11 am to 2 pm, most restaurants will be packed with a mix of locals and tourists, followed by the fleet of small trucks that replenish eateries for dinner service; by 5 pm, the office workers begin clocking out and either depart via the station or linger around it for dinner; at 8:30 pm, most department stores close, and the streets are flooded with an exodus of exhausted office workers, tourists hauling transparent duty-free bags, and young locals who are on a night out; at the same time, promoters of restaurants and clubs begin to position themselves along the main circulation arteries to publicize their businesses and entice potential customers, often in ostentatious cosplay or loitering inconspicuously before abruptly intercepting their unassuming targets; as dinner service concludes and nightlife begins, Kabukicho and Golden Gai become sites of spectacle and overstimulation, where hordes of people slowly proceed up and down the streets and alleys; the claustrophobia dissipates as people file into the station to catch the night trains, and the streets are left with small pools of those meandering around, either drunk or smoking or both; these remnants soon too disappear from the streets late into the night, signaling for shops and municipal services to start cleaning up before the cargo trucks show up the next morning. This sequence is, of course, only one of many concurrent narratives unfolding during a (repeating) 24-hour cycle, and it excludes a menagerie of agents, serendipitous events, or illicit back-alley affairs that complicate narrative linearity. But it illustrates the impossibility of arresting Shinjuku’s urban condition within a single image given that the physical realm is undergoing perpetual transformation.

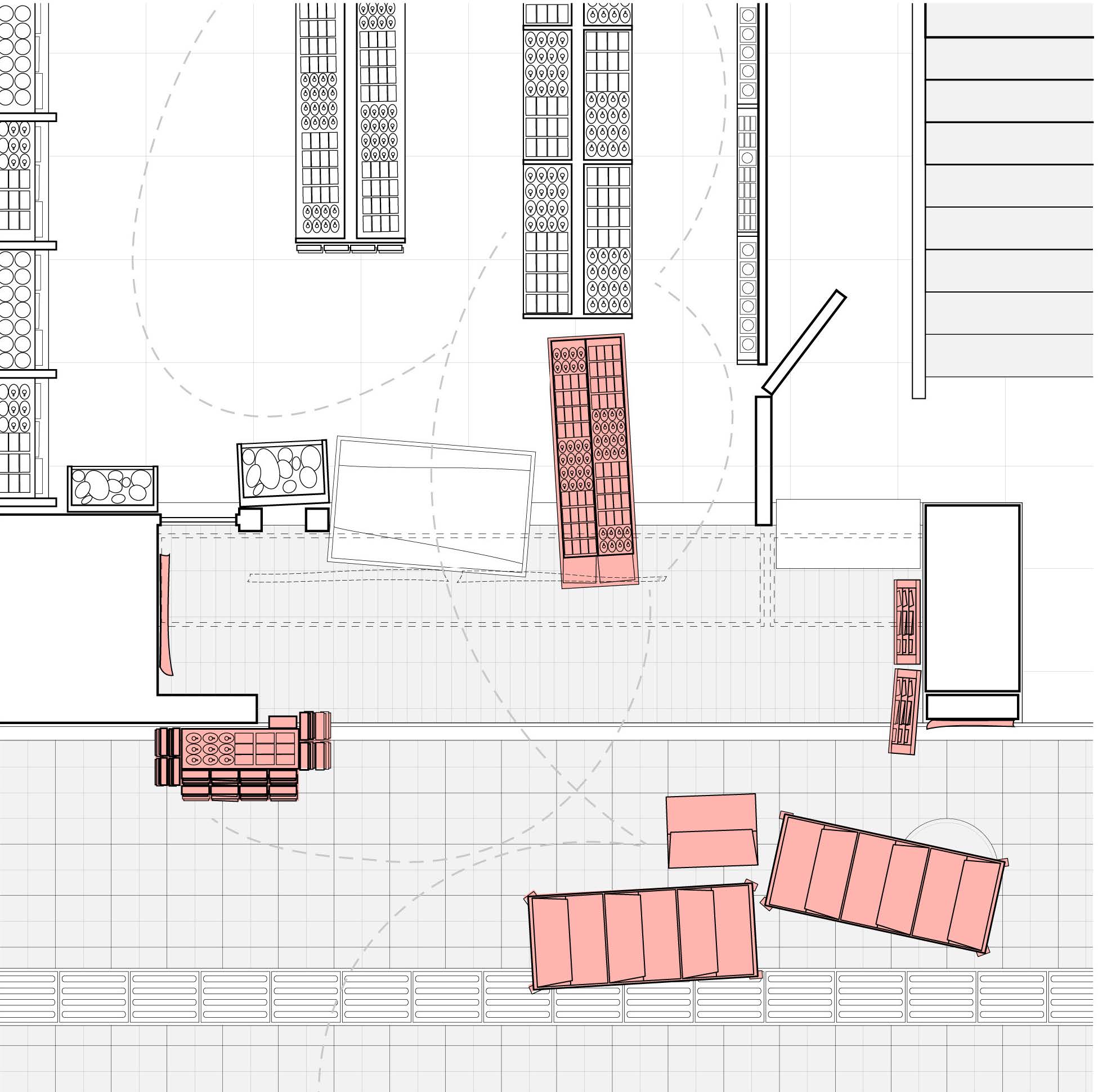

In Shinjuku, schedules and the corresponding movement of bodies trigger incremental shifts in use, which manifest themselves via the routine reorganization of space and can be characterized through architectural analysis. These physical transformations are traces of occupation, and by comparing various configurations generated by different demographics, a system (or even syntax) that can specify the operative qualities of physical elements that alter textual codes of socialness emerges. However, the mediation between mental reflexivity and its indexed effect requires physical labor, which is often negotiated in the in-between spaces of private interiors and public streets. In an analysis of the threshold between alleys and private dwellings, Yoshitsugu Aoki and Yoshiharu Yuasa noted that the perceived enclosure of open spaces immediately outside the home justifies its territorialization for private use. They surmise that the territorial act of Afuredashi (translated as overflow) reflects a human desire to act on their environments and that a meaningful environment is only created through interventions beyond what designers and planners have initially prescribed.[3] Satoshi Sano, Ivan Filipović, and Darko Radović further suggest that “non-functional space is easier to use due to their lack of a designated function” and the informal privatization of the public street produces a “common space” that encourages social interaction between neighbours.[4] The production of in-between-ness through Afuredashi is also seen in the commercial context of Shinjuku. Storefronts of small, independent enterprises are continuously reconfigured in response to the change in street density from routine events. The following observations and analysis will scrutinize the post-occupancy design of artifacts, surfaces, and apparatus that all point to the emergence of a shared reflexivity mentality.

A common occurrence in Shinjuku is the display shelf on wheels, which produces the most obvious form of commercial Afuredashi by extending the interior experience of a store into the circulation of the street. The mobile shelves and carts make visible both the materialization of fast consumerism and the labor processes behind the enterprise. The typical pharmacy, for example, uses three types of mobile ‘shelves’ to signal the different conditions of the logistic-to-consumer cycle, each having a different perceptual prominence at different intervals throughout the day. Before the store opens for business, trucks arrive with heaps of cardboard boxes filled with new inventory, at which time the pharmacy worker emerges and starts stacking them into large cage trolleys. Smaller, miscellaneous packages are put in modular plastic crates that are stacked on top of each other. It should be noted that the pharmacy worker is not a pharmacist but more akin to a salesman. Pharmacies in Shinjuku also tend to employ foreign students who speak Mandarin or English to accommodate the large number of overseas tourists who frequent them. The boxes they push around are all standardized and anonymous, with only a few lines of text providing identifiable inscription. The assemblage of stacked black boxes stresses the impression of sheer quantity, to an extent that the content inside matters less than the image of these bountiful towers of anonymous crates being slowly wheeled into the store. As such, their placement outside the storefront is as much performative as it is pragmatic.

The pharmacy worker begins unboxing in the backroom, behind public view, and products are then assimilated onto their designated spots on the various shelves. Yet the array of shelves does not emphasize an artificial infinity like those of Rem Koolhaas’s Junkspaces; rather, they partition and organize the interior as circulation. Instead of a clear hierarchical layout of subdivisions, the shelves produce tight alley conditions that conduce movement and serendipitous encounters for the tourist who is window shopping. Yet the arrangement is sufficiently fragmented that if a local needs to expediently retrieve a certain product, they can reach it directly based on a common sense of how indigenous organization conventions work. The first order of reading the pharmacy’s spatial composition is based on curating the experience of a foreign entity, whereas a second-order reading reveals normative structures of social life in the Japanese context. The organization of shelves is therefore reflexive, as it anticipates a different set of behaviours based on presumptions of how different demographics would decode the space.

But most intriguing is the third set of shelves that are placed along the storefront, parallel to the street. Small modular baskets are assembled into a shelf that blocks out certain parts of the threshold to produce tighter entries to the side. By limiting the turnover rate of patrons, the store can modulate the interior circulatory experience. More importantly, it produces a surface condition that is intensely signifying, where a passerby views the entire storefront as a microcosmic mass spectacle. It realizes the potential and possibility suggested by the cardboard boxes as an image of overabundance. Taped onto the baskets are flashy signs that announce daily discounts for products that are already quite affordable, as stressed by the price tags in heavy bold font. The image of overabundance is continued on the sides of the shelf as numerous racks of products are hooked onto and spill off the already densely populated baskets. The gatchapon aesthetic encourages an expedient ‘grab-and-go’ consumption culture of commuting office workers, which, not unlike the convenience store, is evidenced by the selection of products tending towards daily necessities such as lip balms, cleanser wipes, and energy drinks. The baskets are sufficiently filled to dispense the need for a worker constantly attending to them, and their almost-transgression into the public street puts them within the continuous flow of potential patrons. A second order, and more obvious, reading of this oversaturated facade is its allure to the passing tourist, who is compelled to reach the 5000 yen national threshold of tax exemption once they start picking up products indiscriminately.

As mentioned, the practice of Afuredashi is unapologetic about making territorial claims of the public domain, and the basket carts would sometimes be disassembled into smaller modules that are wheeled out beyond the boundaries of the storefront. Some are temporarily positioned in front of unused surfaces of abutting buildings, extending the function and visual identity of the store out into common space. Often found above these mobile units are wall mounts that are hooked onto indents or extrusions on the façade. Some storefronts without a window display might then opt to showcase products by attaching them on S-hooks, which could be hung on wall mounts or suspended from the ceiling. This palimpsest aesthetic is rather common along the alleys of Yasukuni Avenue, where the large-scale buildings of 3-Chome and smaller zakkyo buildings from Kabukicho mix.

The modular wall mounts form a gridded matrix of objects that is not dissimilar to the composition of signage and billboards found in the wider context. Zakkyo buildings will have, either above the entrance or the side, a grid that indicates what establishment occupies each floor. Some of these are just logos, while others are more stylistic promotional images or banners, but all of them are direct and precise in their delivery. This graphical grid of icons produces a mental reconstruction of the building’s vertical layout and encodes an expectation of what the visual identity and tone of each floor might be, as if one can look right through the façade covered up by all the signage and right into a colorized section cut of the building. This is a reflexive strategy that effectively organizes the chaotic, and sometimes precarious, business models in Kabukicho. However, the ascribed grid can also be found in multinational brands in 3-Chome and the station area because, as a graphical strategy to signify a building’s parti, it is inherently neutral and is only activated when quadrants on the grid are occupied by referents.

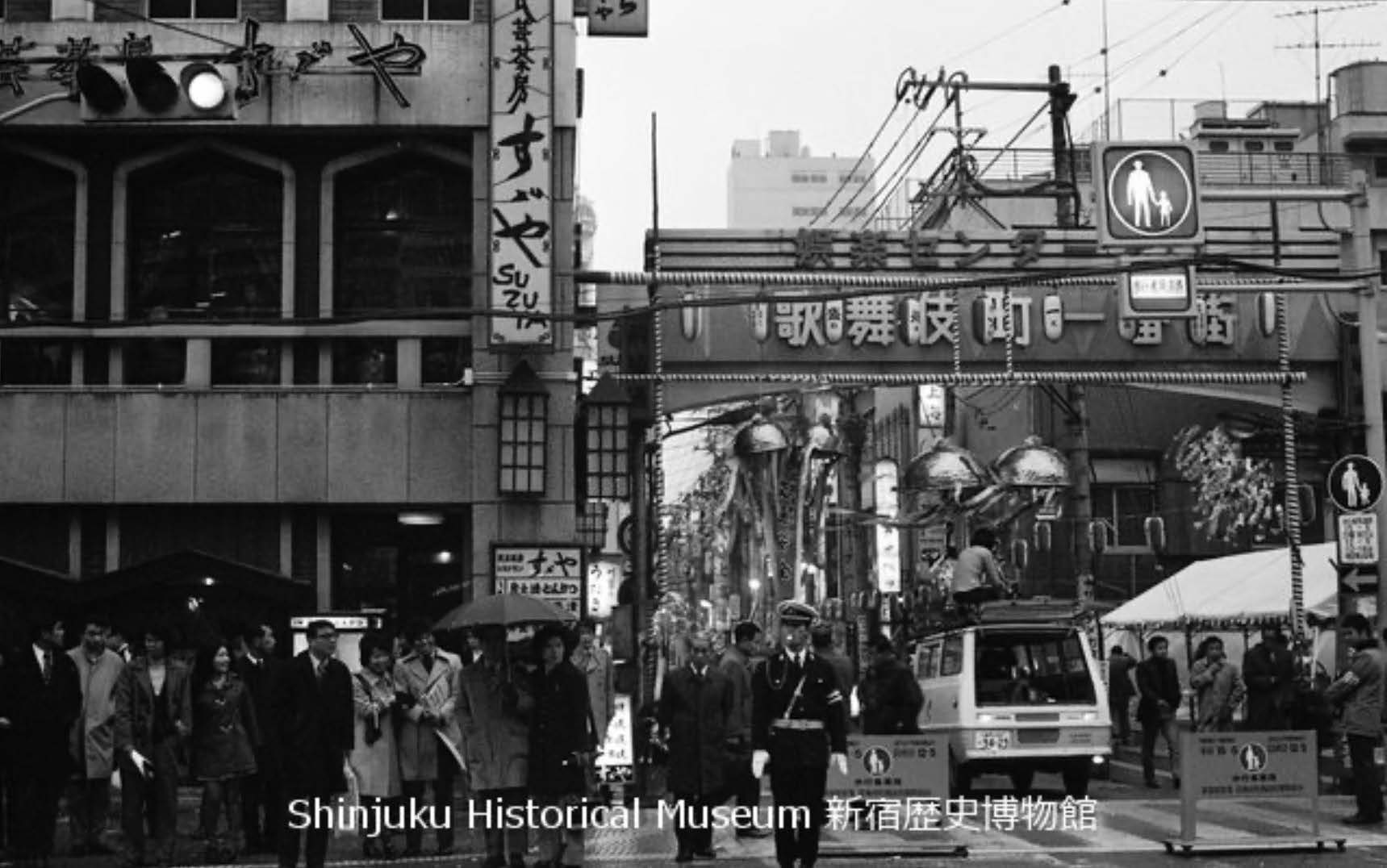

A more assertive example of commercial Afuredashi is found in the three-dimensional extrusion of the storefront onto the street. Some roadside eateries and izakaya have awnings that extend above the storefront, projecting an implied extended territory that is open for territorialization. During evening rush hours, some establishments with outdoor dining will more explicitly enclose that in-between space using curtains and ad hoc furniture. They produce an architectural third space that is defined by its transience and conditions of exception. The temporary influx of foot traffic on the street coincides with the evening rush hour as office workers depart and department stores begin to close, and through various mechanisms concentrate the discharge of people towards Kabukicho, where most establishments operate late into the night. One such mechanism is the implementation of pedestrian-only streets, which is indexed through small red roadblocks that are typically stored in cabinets embedded in various underground entrances during the day with other street furniture. Though their primary function is the negation of vehicular traffic, they serve an unintended secondary function as social condensers – people loiter around these mini-landmarks as they wait for their acquaintances on the periphery of Kabukicho. This produces pockets of spatial viscosity along the urban thresholds that are typically marked by the stylistic gates which announce the territory of Kabukicho along Yasukuni Avenue.

The roadblocks, as objects, also attract coalescence due to their relation to the human scale, where it is just the right height for the body to lean or perch on it as a bench. They encourage interpretive use, but their surface and materiality both discourage long-term misappropriation. The roadblock does not simulate itself as a bench nor does it cease its signification as an apparatus of governance. But the ontology of urban apparatus, specifically in their relation to ergonomics, reveals a deep structure of labour and material exchange that is indispensable to the reflexive operations of Shinjuku. The display shelves in the pharmacy, or any other retailer, require the installation of wheels and locks that allow their mobility throughout the day. They shift position and orientation to face the flow of people and are brought back in at night to be stacked up against each other when the store closes and the shutters are pulled down. Some of these shelves are customized for the storage and display of specific products, like shoe boxes, and would require additional labour in their production. They are 'handmade ready-mades' that give the illusion of standardization when large quantities are placed together as a series. Yet both their initial production and daily utilization are highly idiosyncratic, requiring an equally anonymous labourer to attend to them, all the while making-believe that they are hypermodern objects that aspire to have their own modular autonomy. Organic reflexivity as a mentality and its material reality still requires the human body and its labour as a mediator and facilitator. More often than not, these implementations are surprisingly quotidian, to put it formally, or ad hoc, to describe it realistically. One of the apparatuses involved with the wall mount displays stuck onto exterior facades is a retractable post with an S-hook or clip taped to its end. Store workers will use the post to lift and affix the wire wall mounts onto the wall, and then hang individual items. They stay on the walls until closing when workers once again come out and detach the products and wall mounts before stacking them up inside. This is to say that although there is nothing inherently wrong with the idealization of a reflexive model, one must also acknowledge the informality and labour processes that are required, and therefore should caution against displacing these local elements in the process of hegemonic growth.

The built environment and the city’s social life are engaged in a feedback loop, where architecture only produces a possibility for habitation, and the territorial stake and struggle of its inhabitants alter or diversify those possibilities for symbiosis. Kabukicho has retained its unique identity not by sheer resistance against the encroaching development of large-scale corporations, but by leveraging its difference as an asset that asserts its own indispensability within the larger vision of Shinjuku. The act of othering or imagining alterities can be dangerous in its production of power asymmetries; however, by privileging an urban system that is anticipatory rather than reactionary, aporias can begin to present new alternatives of sustainable developmentalism.

notes:

[1] Smith, Henry D. “Shinjuku 1931: A New Type of Urban Space.” In Cartographic Japan, 158–62. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021.

[2] Lippit, Seiji M. “The Postwar Black Markets and Their Legacy.” In Sharing Tokyo: Artifice and the Social World, edited by Moshen Mostafavi and Kayoko Ota. Actar Publishers, September 2022.

[3] Aoki, Yoshitsugu, and Yoshiharu Yuasa. 1993. “PRIVATE USE AND TERRITORY IN ALLEY-SPACE : Hypotheses and tests of planning concepts through the field surveys on alley-space Part 1.” Journal of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Engineering (Transactions of AIJ)449, 53.

[4] Sano, Satoshi, Ivan Filipović, and Darko Radović. “Public-Private Interaction in Low-Rise, High-Density Tokyo. A Morphological and Functional Study of Contemporary Residential Row-Houses.” The Journal of Public Space, no. Vol. 5 n. 2, 2020, 76.

[1] Smith, Henry D. “Shinjuku 1931: A New Type of Urban Space.” In Cartographic Japan, 158–62. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021.

[2] Lippit, Seiji M. “The Postwar Black Markets and Their Legacy.” In Sharing Tokyo: Artifice and the Social World, edited by Moshen Mostafavi and Kayoko Ota. Actar Publishers, September 2022.

[3] Aoki, Yoshitsugu, and Yoshiharu Yuasa. 1993. “PRIVATE USE AND TERRITORY IN ALLEY-SPACE : Hypotheses and tests of planning concepts through the field surveys on alley-space Part 1.” Journal of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Engineering (Transactions of AIJ)449, 53.

[4] Sano, Satoshi, Ivan Filipović, and Darko Radović. “Public-Private Interaction in Low-Rise, High-Density Tokyo. A Morphological and Functional Study of Contemporary Residential Row-Houses.” The Journal of Public Space, no. Vol. 5 n. 2, 2020, 76.