Memo 016

Infinitude in Reflectivity.

Between Material and Perception: An Alternative Dialectic for SANAA in the Age of In-formation

Nicholas Chung, 18 March 2024

*Optional Pre-req: Eve Blau’s “Tensions in Transparency” [click here]

“In order to think about the information society there seems to be a relationship to the idea of dimension or the effect of the mass or the volume on us. But it also relates to the reflective quality of glass as well, as opposed to its transparent quality.”[i] Sejima Kazuyo, El Croquis, 2000

In an attempt to resolve Sejima Kazuyo and Nishizawa Ryue’s (SANAA) dialectical logic of information and experience, Eve Blau proposes transparency as the operative logic behind the process and projects. Blau remarks that the works exhibit a disagreement between organizational clarity and experienced ambiguity, and that SANAA accentuates this aporia as a simultaneous condition which in turn justifies the diversity of experiences as the inevitable propensity of their compositional dispositions. The material protagonist in Blau’s analysis is unmistakably SANAA’s deployment of glass – both conceptually and materially. The interplay of “functional” and “visual” transparency is first explicated in the 21st Century Contemporary Art Museum in Kanazawa, with the former establishing a field condition between independent programs and the interstitial spaces that interweaves then, whilst the latter contradicts that organizational clarity through the material layering of visual stimuli.[ii] Blau posits that this ‘fuzziness’ results from the high degree of abstraction that Seijima and Nishizawa ascribe to their programming, which privileges open-endedness that is reified through the architecture’s optical ambiguity in spatial depth.

“What is interesting and instrumental about the way in which this transparency operates is that it reveals the contradiction between information and experience without resolving it. In fact, by making visible the conflict between these two modes of knowing the architecture, the transparency between them continuously opens the work to multiple readings.”[iii]

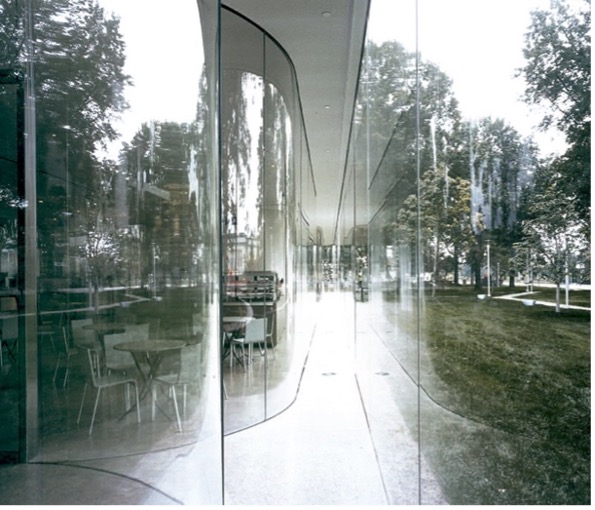

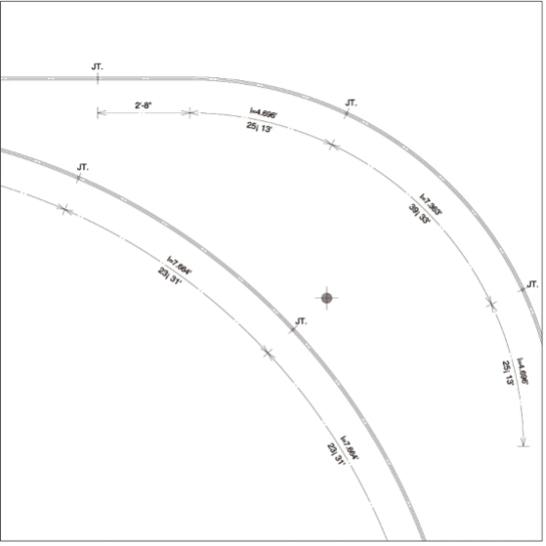

Blau references Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s “abstract space” as a referent in understanding the effects of “thickening and deepening” space and time[iv], but would also caveat that film and montage are inadequate conceptual bases for they are unable to access the sensorial or “haptic” dimension of architecture. She therefore offers Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion as another example of optical ambiguity triggered by the subject’s movement. The rationalism in composition is destabilized by the playful subversion of materiality and thinness without compromising the integrity of the design’s conceptual totality. In SANAA’s projects, you are assured such totality exists without needing the visceral presence of its centering force. In the Toledo Glass Pavilion, the layering of curved glass surfaces accentuates the relational quality between volumes that are not supposed to have a precise boundary between them. It produces an “opacity that one can see through” which Blau argues projects a democratic form of transparency and free oscillation between different experiences. However, if one were to seriously consider the visual effect of layered curving glass, the opacity that Seijima describes is generated through the refractive distortion of light that actually discourages a clear line of sight. One is not supposed to see through the building, but rather see along the edge of the glass walls. In the same manner Blau proposes that SANAA operates in the dualism of clarity and ambiguity, the materiality of glass operates in both transparency and reflectivity. I would argue that it is in reflectivity that one finds a more convincing gesturing towards infinitude, rather than an overly convenient desire for enclosing totality.

The opaque feeling achieved in Toledo is heavily attributed to the instances of instability when there is a slight flare or flicker due to the refraction. The glass works as an image screen, in Lacanian terms, that both object and subject are projected onto, and then extended as a panoramic through the curvature of the edge that brings in elements from the periphery. You can see what is immediately beyond the glass, but your own reflection is also superimposed onto the image, which is then reified in the doubling of glass panes. The layering also allows the exterior to unfold into the interior as partial images, or better yet, images-in-formation as the subject’s body is moving through the glass volumes. The reflections then begin to warp as you move closer or further away from the curved edges of each room. This optical overlay of outside and inside is a result of the innate properties of curving glass, best explicated in Grace Farms in New Canaan where architecture and landscape become indistinguishable when walking along the building’s edge. Another property of glass is such that transparency increases with more light, but it becomes more reflective in the shade. (The reason why your window acts like a mirror at night is because the light inside is much stronger than outside) The delamination of glass layers in Toledo then expands the distance between the subject’s gaze and the projective surface, where the viewing and moving body is implanted into a panoramic-esque collage that fluidly and perpetually re-stitches the park outside, the spaces within, and volumes beyond.

Reflection also sustains a visual hallmark commonly found in SANAA’s works: dematerialization. In the Naoshima Ferry Terminal, what seems to be planimetrically didactic and transparent is complicated by the rhythmic splicing between glass and mirror. The terminal is laid out as a regular column grid with a large flat roof covering three glass volumes and seven mirror panels. The glass volumes cannot hide their physicality any more than they already do, and as such SANAA opts to dissimulate their adjacencies instead by warping images of the real throughout the spatial experience of moving from one end of the terminal to the other. The architecture dematerializes into this field of reflective confusion without fully disappearing, attaining a type of opaque ephemerality that does not fully rely on the transparency of glass. Even with the Barcelona Pavilion, when leaned up against the marble or glass, one begins to notice reflection and redoubling of partial images as extended continuities ad infinitum.

However, it should be noted that Blau’s use of “experience” might not be an adequate descriptor of SANAA’s intent, and Nishizawa would instead suggest objective “perception” as a more appropriate descriptor of their method since “the way we talk about experience is not really how an individual human body senses things, because that is so dependent on whether you happen to be in a bad mood, or the sun is shining and it's good weather.”[v] Sejima would elaborate that their architecture is considered through the circumstances in which they appear, and that appearance has economic, aesthetic, cultural, and environmental determinants. When considered as such, SANAA’s architecture as field conditions is better understood as reflexive conditioning devices that produce an alternative type of seeing and knowing. In Naoshima, rather than Moholy-Nagy’s notion of an abstract space, what we see is more akin to what Theodore Adorno calls a speculative moment. At Naoshima, objectivity is put in positive doubt as you can never quite tell if you are looking at the horizon between columns or a reflection of the horizon behind you in the mirror. These momentary disjunctions begin to destabilize what at first seems to be a transparent and assuring representation of reality as an illusion. At Toledo, this effect is much more severe when considering what the layering of glass obstructs, particularly at those moments of refraction or reflection. Though the thinness and minimal placement of columns are tectonically achieved by an innovative structural grid design, their visual ambiguity in physical space is heightened by the veiling and warping of adjacent glass that first re-doubles its image, then confuses it as part of the mullion system to dematerialize it altogether.

The argument for material reflectivity as a producer of perceptual effect is possibly most conceptually pronounced in SANAA’s intervention at the Barcelona Pavilion. Acrylic curtains produce a spiral within the Pavilion’s interior which takes the reflective play already present and aggressively compounds their circumstances of appearance into a ubiquitous sensation. Here, in the absence of even columns or mullions, one finds the pure enjoyment of the ephemeral architectural boundary through optical distortions which unconceals perception’s own artifice and simulation. Material specificity is denied by the intensification of visual information that autonomously travels through the acrylic curtain across defined architectural components.

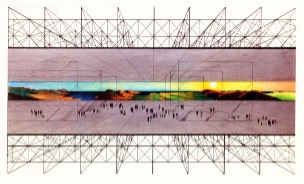

To quickly summarize where we are: reflectively undermines the clarity of transparency by introducing refractive disturbance to draw awareness to the artifice of such transparency; reflectivity elevates the glass to a picture plane where both subject and object meet; reflectivity deployed with curvature captures adjacent scenography onto the same surface, thereby enacting a scenographic infinitude that bypasses, or even explicitly breaks, architecture’s material limits. The obvious follow-up question would be: Why? One might begin to unravel SANAA’s biases through Sejima’s interest in an “information society” quoted at the beginning of this essay. In Blau’s quotation of Sejima from the same El Croquis interview, she adds that “information society is mainly about not seeing,”[vi] which when considered not as ideological or conceptual play but rather the mechanical production of “effect”, is evidence of a deeper consideration in the material properties and the representation of a mediatic intensification in modern life. The term “information society” came into popular usage with the publication of economist Yujiro Hayashi’s book The Information Society: From “Hard” to “Soft” Society (“Jōhōka shakai: hādo na shakai kara sofuto na shakai e”) in 1969[vii], which was part of a larger discursive fascination in media theory during the runup to the 1970 World Exposition in Osaka. There is a rhetorical emphasis placed on architectural space as media systems of communication as screen-based culture becomes both the material fallout and managing antidote to a visual environment miasmically bombarded with unfiltered sense data.

The use of reflection in SANAA’s projects recreate this continuous overload of stimuli as illusive partial images that are in-formation one moment and dissolving in the next. The architecture is not made of parts that form a whole, but rather in each part one can peek into an implied infinitude vis-à-vis their inability to arrest and make intelligible the compounding of visual data. The works do not distort reality itself, but instead distort our perception and consumption of it as images that are glitched or unstable. We enter an uncanny space, or a “sphere of illusion” in Martin Seel’s terms, that exists adjacent to and references general continuity. At Toledo or Grace Farms, the perceptual continuity of the external bleed into the interior environments in such an ambiguous way that it is almost as if the interior glass volumes contain microcosmos of the landscape outside. If not for the haptic awareness of air conditioning or opening and closing doors, one might not even notice the transgression across boundaries. Yet once you are inside the building, the reflection of the interior superimposed onto the landscape beyond starts to signal the same type of infinite ubiquity seen in Futurist provocations like No Stop City or the Continuous Monument. They all point to a concurrent excitement and anxiety of the effects that the oncoming information society will have on the bodily perception of self in space. An infinite interior will project out from us and begin to territorialize and condition the world around us to first digest, then reconstitute the real as its own facsimile. The material boundary as a signifier suspends its own signification, which is cognitively delaminated and pushed out to the furthest extents of the field beyond in landscape projects like Grace Farms, or in the doubling of glass panes as seen in Toledo. In any case, the glass in SANAA’s work is there, but not there; it is somewhere, but it might also be nowhere.

notes:

[i] Sejima Kazuyo quoted in Alejandro Zaera, "A Conversation with Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa," El Croquis 77, February 2000, 14.

[ii] Eve Blau, “Tensions in Transparency: Between Information and Experience: The Dialectical Logic of SANAA’s Architecture,” Harvard Design Magazine, no. 29, fall/winter 2008–9, 31.

[iii] Ibid, 31.

[iv] Ibid, 33.

[v] Nishizawa Ryue quoted in El Croquis 77, 11.

[vi] Sejima quoted in El Croquis 77, 14.

[vii] William O. Gardner, “1970 Osaka Expo and/as Science Fiction,” Review of Japanese Culture and Society 23, December 2011, 33.

[i] Sejima Kazuyo quoted in Alejandro Zaera, "A Conversation with Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa," El Croquis 77, February 2000, 14.

[ii] Eve Blau, “Tensions in Transparency: Between Information and Experience: The Dialectical Logic of SANAA’s Architecture,” Harvard Design Magazine, no. 29, fall/winter 2008–9, 31.

[iii] Ibid, 31.

[iv] Ibid, 33.

[v] Nishizawa Ryue quoted in El Croquis 77, 11.

[vi] Sejima quoted in El Croquis 77, 14.

[vii] William O. Gardner, “1970 Osaka Expo and/as Science Fiction,” Review of Japanese Culture and Society 23, December 2011, 33.