Memo 015

Binaries and Pairs: Unintended Resonances and Discrepancies in Chinese Landscape Gardens and Structuralist Thought

Nicholas Chung, 28 February 2024

*Pre-req readings: The Structural Study of Myth by Levi-Strauss, Structure, Sign and Play by Derrida

In his essay "Memory, Direct Experience, and Expectation," Stanislaus Fung identifies topography, architecture, environmental variations, and the moving body as factors triggering shifts in the readings of spatial depth.[i] In his observations of the central pond of Zhuo Zheng Yuan, Fung attributes the bridge in the middle ground as a narrative device that occludes the embankment in the background. However, a slight forward movement of the observer in the plan would once again reveal the water hidden behind the bridge as the bridge and the embankment optically misalign, increasing the perceived distance between the observer and the far shore. Yet, in the instance where the mass of the bridge obscures the water behind it, spatial depth is momentarily compressed. This optical play of concealing and un-concealing, characterized by Fung as instability, is predicated on a looseness by not fastening the definitions of near and far as a static binary: though one is metrically moving closer to the opposite shore in plan, the act of un-concealing consciously reaffirms that one is moving further away in perspective. There is a glaring temptation to say that this is the same type of looseness that Derrida characterizes as play in his critique of Lévi-Strauss’s Structuralism. This essay will entertain this temptation and suggest possible resonances whilst underlining some unreconcilable slippages between the two modes of thought.

Fig.1 Bridge obscuring embankment in Zhuo Zheng Yuan.[ii]

Fig.1 Bridge obscuring embankment in Zhuo Zheng Yuan.[ii]

Suppose that this optical play takes place in what Martin Seel calls a "sphere of illusion" that is displaced outside general continuity,[iii] as a territory that one consciously decides to transgress, thereby engaging the subject with the “aesthetics of being” and reaffirming the object’s “aesthetics of appearance”, which paired together is then stipulated as a larger “aesthetics of appearing."[iv] This imposes a mutual responsibility in the art and its observer when constructing an experience that Theodore Adorno would call a speculative moment, which is to ascribe a positive meaning to the mediating subject’s destabilization of the object, or objectivity itself. In Structuralist thought, each signifier occupies a static position that is defined only through diacritical negation – ‘raw’ can only mean ‘not cooked’ or ‘not pickled’. However, the use of pairing in Chinese philosophy necessitates a specific self-hood to establish relativity. To engage in a play between ‘mountain’ and ‘water’ requires ‘mountain’ to be understood with a certain dexterity from the observer as its relation to other elements change. This dexterity, or affordance, is projected by the object upon the subject, not dissimilar to what Bernard Tschumi calls cross-programming in his architectural work: the misappropriation of a roadblock as an ad-hoc bench is anticipated as the autonomous choice of an individual. Play therefore comes from a capacity to be freed from the process of forming.

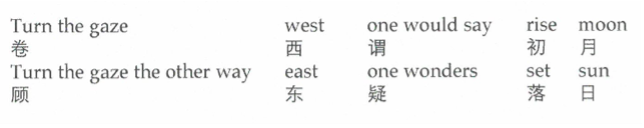

However, that is not to say that the Structuralist method is inapplicable to the reading of Chinese aesthetics. Binaries and pairs are both processed as synchronic experiences, as exemplified in François Jullien’s examination of syntactical parallelisms found in Chinese poetry and Levi-Strauss’s deployment of the Oedipus myth.

Fig.2 Jullien's citation of "Deng yongjia Lüzhang shan" and Levi Strauss's deployment of the Oedipus myth both reveal a desire to unpack diachronic compositions synchronically.

Though the ‘text’ is embodied, literally, in a linear format, the vertical bundling of individual elements facilitates a comparison that then insinuates a deeper (unconscious) structure emerging from mediation. This mediation in Structuralist binaries is metonymic, but is analogous in aesthetic pairs for the Chinese. For thinkers like Levi-Strauss, an expanded field condition of differences can encapsulate an unconsciousness that is total. Whereas pairings in Chinese aesthetics suggest a faraway that is infinite. This chasm is underpinned by an inherent difference between Hegelian determinism and Buddhist sensibility – the former universalizes language to satisfy a desire for a reassuring static whole with clear scalar hierarchies, whereas the latter treats each signifier as a jewel[v] that is to connected to, and also reflects other already-self-assured signifiers. A world of infinitude extends beyond the walls of the Chinese garden that is also reflected in individual elements that reveal "the operation of the world in its entirety."[vi] To borrow an extra-Chinese example, Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki describes the concept of ‘oku’, which suggests a centripetal inwardness rooted in similar schools of thought, as a phenomenon that reflects the natural order in the urban environment. Maki notes that “the Japanese have long seen small spaces as autonomous microcosms and thus developed the perception that a part was in fact also a whole.”[vii] The conceptual absence of the scalar hierarchy of part and whole (or more accurately, the impossibility of incapsulating a whole) is symptomatic of a larger dexterity that is mobilized in the production of aesthetic experiences across East Asia.

The interchanging (and rather inconsistent) use of looseness, dexterity, and play over the course of this essay thus far points towards the affordances offered in Seel’s “sphere of illusion”, where aesthetic experiences are presented with two opportunities: the completion of hyper-reality and afreedom in infinitude. Firstly, Seel would stress that the experience of an aesthetic object intensifies "the feeling for the here and now of the situation in which perception is executed."[viii] This experience un-conceals the object as hyperreal—or rather, a facsimile of reality—that announces its own boundary. In the Chinese garden, the accentuation of binaries such as near-far, yin-yang, mountain-water is therefore warranted, even expected, as an aesthetic experience entails an awareness on the part of the subject that they are entering the dream-like hyper-real, and that paradoxes in spatial narratives desire to either resolve or negate themselves. Narrative lines in the world of illusion are completely inaccessible to those within the aesthetic experience, and is only made intelligible to and by the external forces that predetermined their propensities[ix] – the tragic hero is never aware of his own hamartia but the audience is cued into the various foreshadowing narrative devices that the playwright intentionally accentuates; the wanderer in the Chinese garden does not know they are walking through an allegorical space where each signifier will eventually find its pair. The pairs are mediated by the second opportunity of affordance – a liberation from meaning. This freedom found in the infinitude of each ‘pearl’ is analogous to the freedom away from metaphysics that Heidegger proposes in Being and Time. If binaries in Structuralist thought are determinate and inherently repellent, occupying opposite sides of the same proverbial coin and never being able to meet, then pairings in Chinese aesthetics produce an indeterminate form(lessness) that is in the continuous process of becoming between two re-reifying possibilities: yin is always becoming yang, mountains are transforming into water, moving near is just another way of seeming far from different vantage point.

notes:

[i] Fung, Stanislaus. “Memory, Direct Experience and Expectation: The Contemporary and the Chinese Landscape.” In Thinking the Contemporary Landscape. Edited by Christophe Girot and Dora Imhof, 246-259. New York: Princeton Architectural Press 2016. Page 253.

[ii] Fung, 251.

[iii] Seel, Martin, 'The aesthetics of appearing', Radical Philosophy 118, Mar/Apr 2003. Page 18.

[iv] Seel, 19.

[v] See Indra’s Net of Jewels

[vi] Jullien, François. Living off Landscape, or the Unthought-of in Reason. Translated by Pedro Rodriguez. London & New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018. Chapter 2. Page 18.

[vii] Maki, Fumihiko. Wakatsuki, Yukitoshi. Ōno, Hidetoshi. Takatani, Tokihiko. Pollock, Naomi. Watanabe, Wakatsuki, Yukitoshi, et al. “Observing the City.” In City with a Hidden Past. Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing Co., Ltd, 2018, Page 23.

[viii] Seel, 19

[ix] Jullien, François. The Propensity of Things: Toward a History of Efficacy in China. New York: Zone Books, 1995. Chapters 1-3.

[i] Fung, Stanislaus. “Memory, Direct Experience and Expectation: The Contemporary and the Chinese Landscape.” In Thinking the Contemporary Landscape. Edited by Christophe Girot and Dora Imhof, 246-259. New York: Princeton Architectural Press 2016. Page 253.

[ii] Fung, 251.

[iii] Seel, Martin, 'The aesthetics of appearing', Radical Philosophy 118, Mar/Apr 2003. Page 18.

[iv] Seel, 19.

[v] See Indra’s Net of Jewels

[vi] Jullien, François. Living off Landscape, or the Unthought-of in Reason. Translated by Pedro Rodriguez. London & New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018. Chapter 2. Page 18.

[vii] Maki, Fumihiko. Wakatsuki, Yukitoshi. Ōno, Hidetoshi. Takatani, Tokihiko. Pollock, Naomi. Watanabe, Wakatsuki, Yukitoshi, et al. “Observing the City.” In City with a Hidden Past. Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing Co., Ltd, 2018, Page 23.

[viii] Seel, 19

[ix] Jullien, François. The Propensity of Things: Toward a History of Efficacy in China. New York: Zone Books, 1995. Chapters 1-3.