Memo 014

Between Modern Frenzy and a Mediated Nature: Casa Prieto Lopez as an Architecture for Transitions

Nicholas Chung, 12 February 2024

Georg Simmel writes at the dawn of the metropolis about the necessity of putting up a psychological barrier to block out the overstimulation of ‘contemporary’ life. This blasé attitude is characterised as the “self-preservation of certain identities” by “devaluing the whole objective world.”[i] The mind produces a gap between self-consciousness and the simultaneous totality of all objet petit a, human and non-human. Lukacs later ascribes a physical dimension to Simmel’s thesis by contextualizing it through the objectification and abstraction of the proletarian body. But just to dwell on Simmel for a bit, he reveals a procedural compartmentalization of metropolitan life that necessitates spatial arrangement:

The whole inner organization of such an extensive communicative life rest upon an extremely varied hierarchy of sympathies, indifferences, and aversions of the briefest as well as of the most permanent nature.[ii]

Domestic spaces of this period reproduce these anxieties experienced by society writ large and function as transitional devices between exterior and interior, foreign and domestic, chaos and control. This paper will speculate on how architecture executes transitions by studying Luis Barragán’s Casa Eduardo Prieto Lopez in Mexico City (1948), focusing on its externality (or lack thereof), its promenade architecturale, and how it reconstructs the external as a mediated image of “the most permanent nature”.[iii]

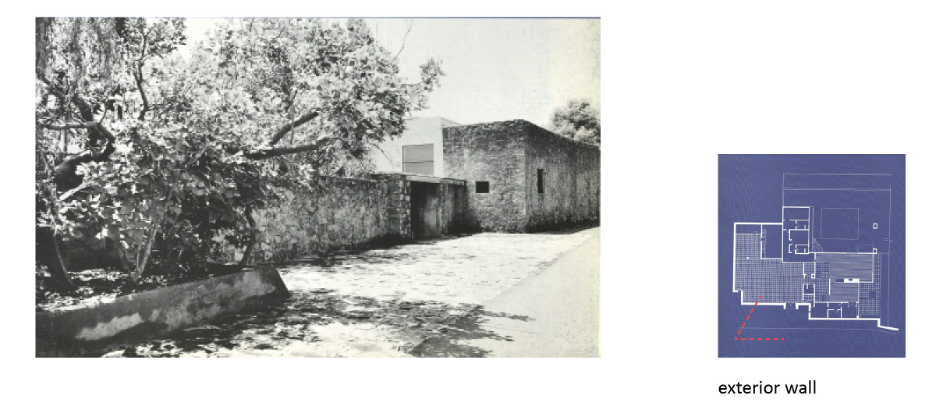

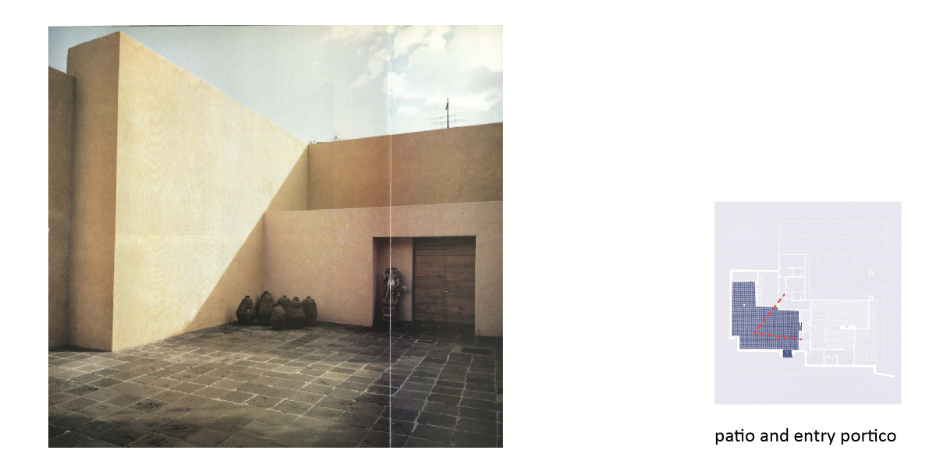

Casa Eduardo Prieto Lopez in its conception has always privileged the exclusion of outside as its priority. The site was selected before the neighborhood was fully urbanized; running water, electricity, and paved streets were not completely installed. Anecdotally, Barragán initially marked the building plot using stones and rocks scattered in the area.[iv]Formally, the house operates primarily in rectilinear housing and deploys a similar sensibility to surfaces with its European contemporaries. The interior façade that faces the garden privileges large panes of glass held by thin steel mullions, a framing strategy for reproducing nature that will be explored later. The façade that faces the street is aggressively mute in its firm rejection of the exterior world. Federica Zanco writes that “Barragán consolidated a language that constitutes a modern reading of traditional Mexican architecture, and in particular, of the commodious, silent and introverted spaces of colonial conventos.”[v] The complex is wrapped around by a high wall of volcanic stone, with an inconspicuous opening that brings one into an expansive patio space. (fig. 1) In it, one is confronted by the subtly colored blank façade of the house proper, with a very gentle stereotomic setback in the volume that signals a portico. Barragán places emphasis on materiality, using organic rockwork that belongs to the external world to enclose territory, and within it using the plastered walls of the house to produce monumental homogeneity. The protruded entry massing is neither axial nor pronounced, and the portico is proportionally divided into three modules, with the center and right panel replaced by a set of unadorned wooden doors. (fig. 2) In its externality, it could be said that Barragán aims to produce an architecture of regression by dematerializing elements of its architectural specificity.

Fig. 1 Exterior wall is constructed of volcanic rock and the house behind it.[vi]

Fig. 1 Exterior wall is constructed of volcanic rock and the house behind it.[vi]

Fig. 2 Exterior view from patio.[vii]

Fig. 2 Exterior view from patio.[vii]

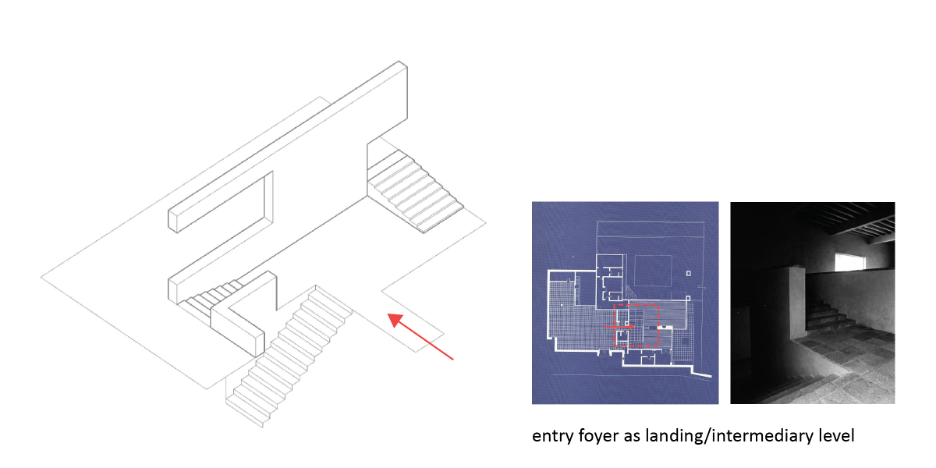

The sequence of moving through a series of thresholds produces a promenade that gradually filters out the external into a distilled interior. Through the tight entryway flanked by two smaller rooms (presumably closets), one enters the foyer that, like the entrance, is neither centralized nor spatially prescriptive. Instead, one is faced with a blank wall that obscures the sectional shifts which compartmentalizes various functional zones. Carlos Martí Arís observes that “the connection between spaces is organized through a focal hall that offers a variety of spatial sequences – both vertical and horizontal – through half stairs, low thick walls that partially reveal and announce, framed and blurred by light, the contiguous space.”[viii] The house disregards the exterior’s preconditions of ground and one enters the house mid-sequence. It can also be said that the foyer doubles as a landing sectionally to emphasize the transitional condition of being in between exterior and interior. (fig. 3) To the north, an adjoining set of stairs leads down into the lower level as well as the main living-dining space elevated roughly two to three feet above ground. Disengaged from the south wall of the foyer is a set of stairs that also ascends to the dining space by going through a small puncture in the wall. However, the stairs here should be read as an ornamental object instead of functional circulation given that Barragán seems to have squeezed the margins in front of the first tread so tightly that it is both frugal and hostile towards the human body if one approaches it as a stair to walk on.

Fig. 3 Axonometric, plan, and image[ix] of entry foyer.

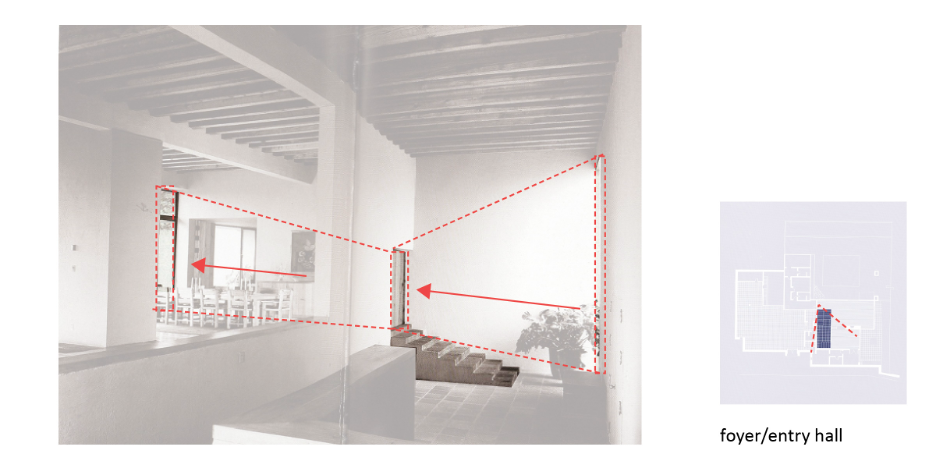

Fig. 3 Axonometric, plan, and image[ix] of entry foyer.This particular sequence as non-circulation is further articulated by the dimension of the opening in the wall. It is much lower than the height of a person and therefore compels alternative consideration of its performative quality beyond the obvious functional meaning. The portal functions instead as a part of a series of frames that go from the patio, through the interior, and back out onto the landscape. (fig. 4) The windows in Casa Prieto Lopez enframe[x] the exterior, the thin mullions offset towards the sides produce a planar hierarchy that compartmentalizes the expansive landscape into limited images. Whilst the promenade into the house is a sedimentary process of excluding external stimuli, by reaching the deep interior one is once again reacquainted with the exterior as conditions of ontological artifice: the framed view and the landscape garden. (fig. 5) The house as an architectural device brings the psychological operation of blasé-ness into the physical dimension, reaffirming the agency of buildings to act on the world and thereby elevating architecture from art to modern machines for living.[xi]

Fig. 4 Alignment of windows and portals create porosity between exterior and interior.[xii]

Fig. 4 Alignment of windows and portals create porosity between exterior and interior.[xii]

Fig. 5 Windows in Casa Prieto Lopez enframing nature as a picture.[xiii]

Casa Eduardo Prieto Lopez is symptomatic of how modern architecture responds to the anxieties of contemporary life, and how the discipline and discourse problematizes then resolves perceived sociocultural paradigm shifts. Barragán produces a domestic environment that preserves the occupant’s self-hood by a procedural devaluation and expulsion of exteriority, using architecture to arrest the explosive inundation of reality by mechanically reproducing it as simulacra. Unlike more articulated or monumental works of Luis Barragán, Casa Prieto Lopez’s parti does not assert its architectural expression for its own representational sake, but is instead operating on a more subconscious level by reconditioning the occupant’s psyche in the transition from exterior to interior.

notes:

[i] Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1903), The Sociology of Georg Simmel, Free

Press: New York, 1950, 52.

[ii] Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life”, 53.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Siza, Álvaro, Antonio. Toca, José María. Buendía Júlbez, Antonio Fernández Alba, Luis Barragán, and Spain. Ministerio de Obras Públicas, Transportes y Medio Ambiente. 1996. Barragán : obra completa. 2a. ed. rev. Sevilla : Mexico: Tanais Ediciones ; Colegio de Arquitectos de Ciudad de México, 125.

[v] Zanco, Federica, and Ilaria. Valente. 2002. Barragán Guide. Birsfelden: Mexico: Barragan Foundation; Arquine + RM, 126.

[vi] Siza. Barragán : obra complete, 127-128.

[vii] Ibid, 124.

[viii] Rentería, Isabela de, and Claudia Rueda Velázquez. 2018. “Transitional Spaces in the Architecture of Luis Barragán and José Antonio Coderch: Casa Prieto López and Casa Ugalde.” Arq (London, England) 22 (3), 199.

[ix] Ibid, 198.

[x] Notion of “gestell” from: Heidegger, Martin. “The Question Concerning Technology” (1954), The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1977), 19.

[xi] Cohen, Jean-Louis, and John Goodman. 2007. Toward an Architecture. Los Angeles, Calif.: Getty Research Institute.

[xii] Zanco, Federica, and Ilaria. Barragán Guide, 130-131.

[xiii] Siza. Barragán : obra complete, 126-128.

[i] Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1903), The Sociology of Georg Simmel, Free

Press: New York, 1950, 52.

[ii] Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life”, 53.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Siza, Álvaro, Antonio. Toca, José María. Buendía Júlbez, Antonio Fernández Alba, Luis Barragán, and Spain. Ministerio de Obras Públicas, Transportes y Medio Ambiente. 1996. Barragán : obra completa. 2a. ed. rev. Sevilla : Mexico: Tanais Ediciones ; Colegio de Arquitectos de Ciudad de México, 125.

[v] Zanco, Federica, and Ilaria. Valente. 2002. Barragán Guide. Birsfelden: Mexico: Barragan Foundation; Arquine + RM, 126.

[vi] Siza. Barragán : obra complete, 127-128.

[vii] Ibid, 124.

[viii] Rentería, Isabela de, and Claudia Rueda Velázquez. 2018. “Transitional Spaces in the Architecture of Luis Barragán and José Antonio Coderch: Casa Prieto López and Casa Ugalde.” Arq (London, England) 22 (3), 199.

[ix] Ibid, 198.

[x] Notion of “gestell” from: Heidegger, Martin. “The Question Concerning Technology” (1954), The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1977), 19.

[xi] Cohen, Jean-Louis, and John Goodman. 2007. Toward an Architecture. Los Angeles, Calif.: Getty Research Institute.

[xii] Zanco, Federica, and Ilaria. Barragán Guide, 130-131.

[xiii] Siza. Barragán : obra complete, 126-128.