Memo 012

The Precarity of Progress and Potential

Nicholas Chung, 22 October 2023

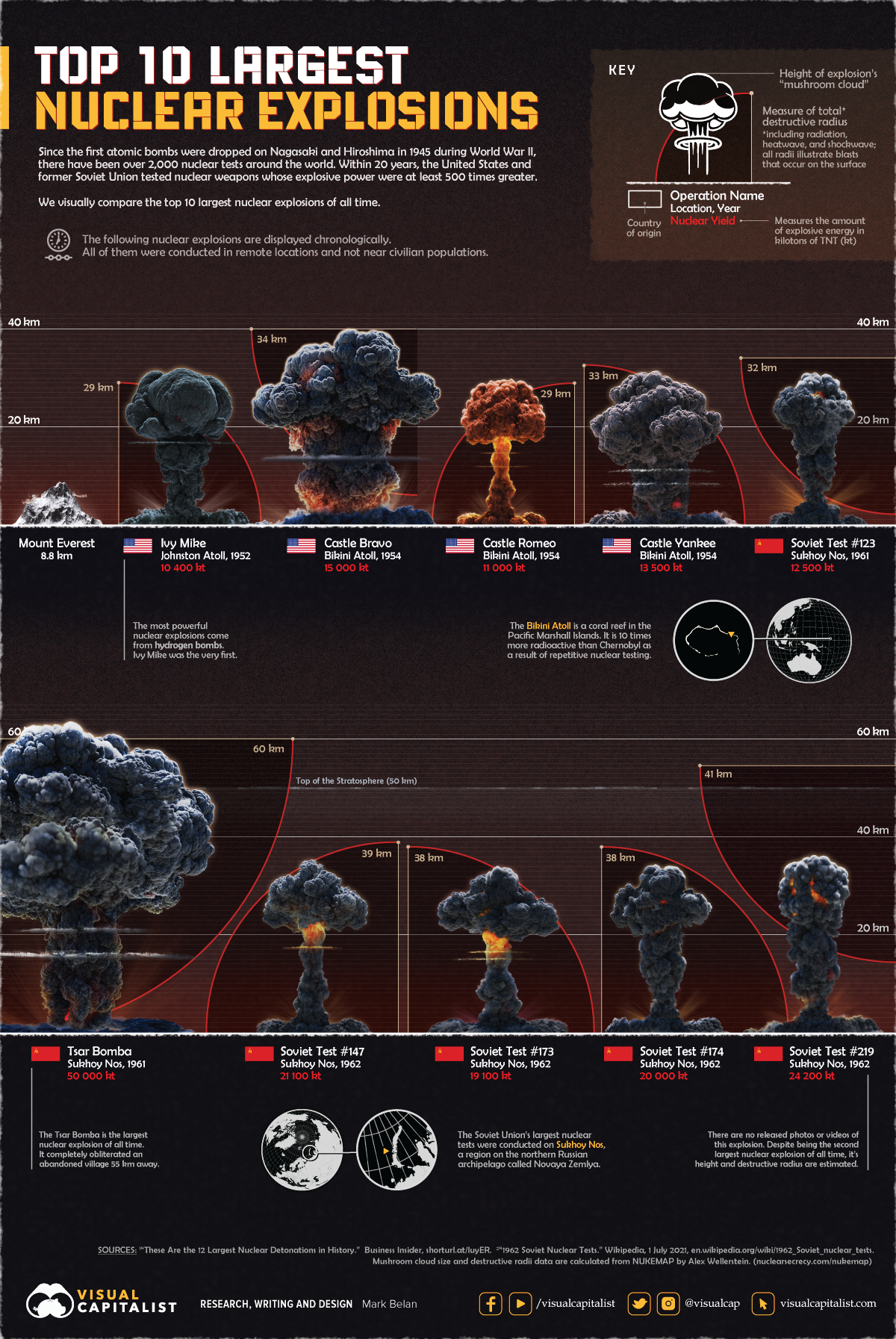

The preverbal mushroom in Anna Tsing’s The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins is unmistakably the atomic cloud that shook the world above Hiroshima in 1945. That said, it is also the mushroom clouds above Los Alamos, the Bikini Islands, Mityushikha Bay, and the potential 12,500 mushroom clouds that have yet to detonate across the world’s nuclear arsenal. Though the moral tension of progress and ethics in the American atomic race has recently been sensationalized in Christopher Nolan’s three-hour blockbuster Oppenheimer, a key narrative thread that also emerged from the film is the precarity of rapid growth and humanity’s incessant rush for even more progress. The scientists of Los Alamos were so engrossed with the target that reflection on their getting there came only when it was too late.

Oppenheimer: “When I came to you with those calculations, we thought we might start a chain reaction that would destroy the world.”

Einstein: “I remember it well. What of it?”

Oppenheimer: “I believe we did.”[i]

In an interview about her book, Tsing characterizes this phenomenon as “narrative blinders” that pinpoint a future where progress is the only possibility.[ii] She would argue that the assumption of progress is the cause of the slew of environmental crises facing the world today. This tunnel vision creates a worldview that normalizes the accelerating extraction and exploitation of resources. Yet what is often unseen as we are immersed in an accelerating world (fueled by capitalism and neoliberal consumerism) is the web of adjacencies that are simultaneously dependent and contingent on our actions. Additionally, what is left unsaid (or rather, what we would not want to acknowledge) is the fragility of the connections we take for granted, the same connections that keep the world running for us. In the same way Matsutake mushrooms would not have grown in Oregon if not for the serendipitous and unlikely chain of symbiotic events that took place (from the existence of pine trees to the right amount of logging, then the conservationist pushback to stop logging so the pine chips that settled on the earth can nourish and privilege Matsutake instead of another varietal, and to its discovery), much of the objects that interface us and the natural world require an entanglement of elastic supply chains. For example, between the origin of managed timberlands in Brazil or Indonesia and the destination of our printers, the production of paper requires agricultural frameworks, fossil fuel extraction, global logistics, marketing… These supply chains stretch themselves in all directions until eventually they reach their elastic limit – and SNAP.[iii] The elastic thread that perpetuates a fetish for progress can break with just the smallest amount of pressure: one cargo ship stuck in the Suez Canal can bring global supply chains to a screeching halt. These moments of exception should force us to pause and reflect on our business-as-usual attitudes toward consumption and to look back onto the debris field that is expelled, excreted, and expunged from the thrust of progress. To exist in this debris field, or the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, first requires an examination of this new nature. Though most geographers and social anthropologists, Tsing included, would use the Anthropocene as a framework, Rem Koolhaas’s Junkspaceoffers a compelling alternative worldview: instead of examining the scars at the sources of extraction, the symptoms of contemporary blight are found in the packaged products ready for consumption, and that our Targets and Walmarts might as well be the nuclear arsenals full of unexploded mushroom clouds for the everyday person.

Junkspace is what remains after modernization has run its course, or more precisely, what coagulates while modernization is in progress, its fallout. Modernization had a rational program: to share the blessings of science, universally. Junksapce is its apotheosis, or meltdown […] Junkspace is the sum total of our current achievement; we have built more than previous generations put together, but somehow we do not register on the same scale.

Continuity is the essence of Junkspace; it exploits any invention that enables expansion, deploys the infrastructure of seamlessness: escalator, air-conditioning, sprinkler, fire shutter, hot air curtain

Mankind is always going on about architecture. What if space started looking at mankind? Will Junkspace invade the body? Through the vibes of the cell phone? Has it already? Through Botox injections? Collagen? Silicone implants? Liposuction? Penis enlargements? Does gene therapy announce a total reengineering according to Junkspace? Is each of us a mini-construction site? Is mankind the sum of three to five billion individual upgrades?[iv]

…food for thought. 🍄

notes:

[i] Nolan, Christopher. Oppenheimer. Universal Pictures, July 2023.

[ii] Tsing, Anna L. “What we Can Learn from a Mushroom.” Brainwash Festival Amsterdam, 2021.

[iii] Capitalized and enlarged for dramatic effect.

[iv] Koolhaas, Rem. "Junkspace." In S,M,L,XL, 123-128. New York: Monacelli Press, 1995.

[i] Nolan, Christopher. Oppenheimer. Universal Pictures, July 2023.

[ii] Tsing, Anna L. “What we Can Learn from a Mushroom.” Brainwash Festival Amsterdam, 2021.

[iii] Capitalized and enlarged for dramatic effect.

[iv] Koolhaas, Rem. "Junkspace." In S,M,L,XL, 123-128. New York: Monacelli Press, 1995.