Memo 010

Contemporary Personas as Mental Image

Nicholas Chung, 03 October 2023

In “Self-Portraiture in the First-Person Age”, Lauren Cornell posits that the strategy for digital existence is either “total retreat” or TMI (Too Much Information). The production of a persona that differentiates from the actual self requires explicit sedimentation of one’s own externality. In reference to David Kolb’s The Spirit of Gravity, one “posits and proclaims such externality as an – external – way of transcending that externality” by fabulating a microhistory that might or might not parallel one’s personal history. Cornell writes that “what it means to present yourself, your body, your autobiography, your day-to-day existence in public has changed […] as the first person has become a default and commercialized mode of presentation.” (Cornell, 8) The distinction between self-perception, the indexical object, the curated subjective narrative, and excreted evidence draws out similar nuances to how Julietta Singh describes the body archive. Only now, the body archive is subject to mass consumption, open for the anonymous audience’s antagonization/ othering as they orient themselves against this sea of infinite artificial personas.

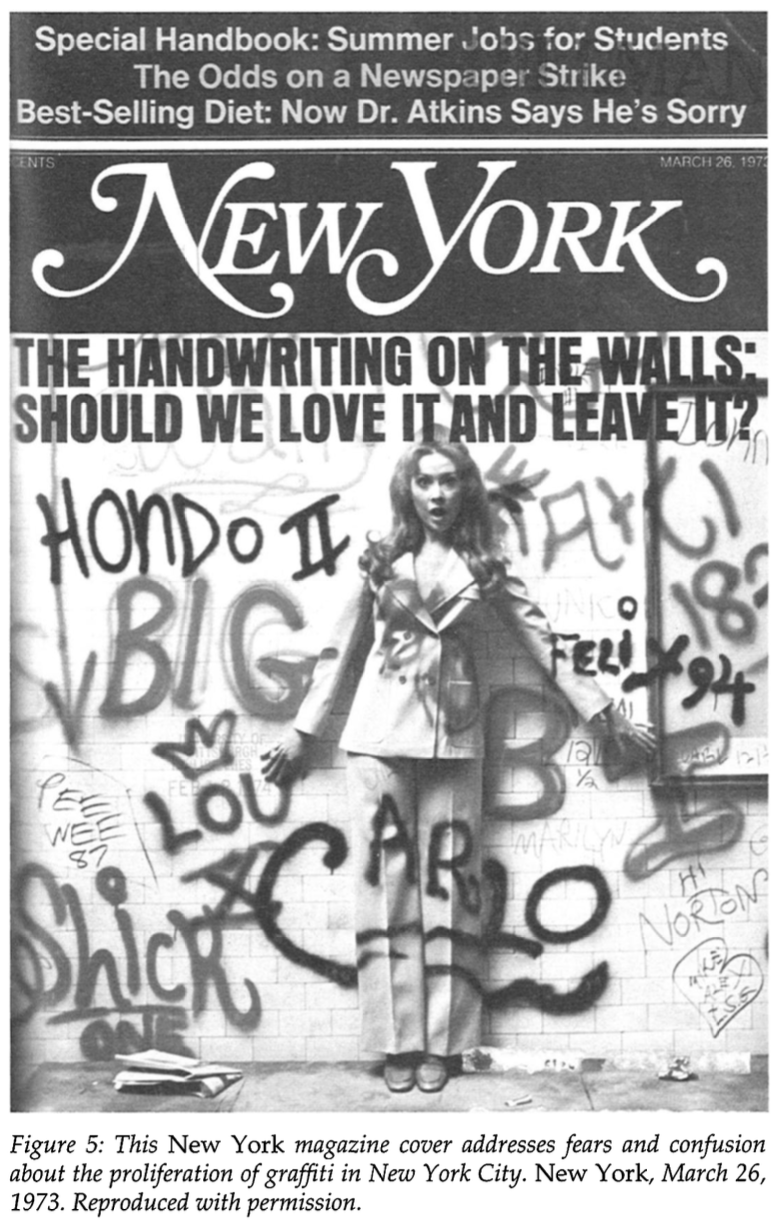

The material practice of personas as images or iconography is also discussed in Rachel Masilamani’s Documenting Illegal Art, in particular through tagging and the problematic of institutional collection. First, briefly on tagging – its performative function of defacement upon surfaces accessible to the public eye reappropriates urban spaces and thereby undermines presumptions of ownership and territory. The ecology of tags also reflects reciprocity and networks within and between communities. But just to dwell on the act of defacement a bit longer, tags as pictograms signal resistance and visibility vis-à-vis iconoclash. It subverts the stable and sterile mental image of authority by attacking the conditional relations that are encoded onto the external surface. Defacing the mise en scene with an alien persona de-neutralizes those surfaces into opportunities for re-appropriation. They are inherently antagonistic in forcing the public domain to confront their inconformity.

Therefore, to propose the active collection and institutionalization of graffiti art is, from a cynical point of view, a way to undermine their precarious effectiveness via legitimization. (by giving them “an everlasting name”) Iconoclash only works when there is something to react to, and graffiti loses its meaning of inscribing when it is isolated from its context. We can look to Keith Haring as someone who straddles the problematic of defacement as high art. He goes into the subway, finds a blank frame waiting for a new advertisement, and when no one is looking begins his spray-painting quickly and spontaneously. His graphic art is highly accessible simply by paying the subway fare and is consciously decentralized for there is no prior announcement or way to know where his work might pop up. His playful iconographic protagonists also produce a weirdly relatable dialectic with his audience. W.J.T. Mitchell writes about The Imago Dei – image “understood not as picture but likeness”, a “spiritual” ideal. (Mitchell What is an Image, 521) But instead of God, Haring’s figures reproduce the likeness of everyday people through an anonymous pictogram. These personas are general enough that Haring’s audience can project themselves into what I would characterize as achievable ideals. This genericness is not unlike what our digital personas are attempting to create today, by either overflooding our feeds to create a pictogram of ourselves, or by not posting at all – the ultimate body of genericness.

image from Daily Art

image from Daily Art

notes:

Maoz Azaryahu, An Everlasting Name: Cultural Remembrance and Traditions of Onymic Commemoration (Oldenbourg: De Gruyter, 2021), 31–88.

Rachel Masilamani, “Documenting Illegal Art: Collaborative Software, Online Environments and New York City’s 1970s and 1980s Graffiti Art Movement,” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, vol. 27, n. 2 (2008): 4–14.

Lauren Cornell, “Self-Portraiture in the First-Person Age,” Aperture, no. 221 (2015): 34–41.

Keith Harring:

https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/graffiti-subways-keith-haring/

Maoz Azaryahu, An Everlasting Name: Cultural Remembrance and Traditions of Onymic Commemoration (Oldenbourg: De Gruyter, 2021), 31–88.

Rachel Masilamani, “Documenting Illegal Art: Collaborative Software, Online Environments and New York City’s 1970s and 1980s Graffiti Art Movement,” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, vol. 27, n. 2 (2008): 4–14.

Lauren Cornell, “Self-Portraiture in the First-Person Age,” Aperture, no. 221 (2015): 34–41.

Keith Harring:

https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/graffiti-subways-keith-haring/