Memo 007

Venturi’s Chippendale Chair

Nicholas Chung, 23 September 2023

Introduction

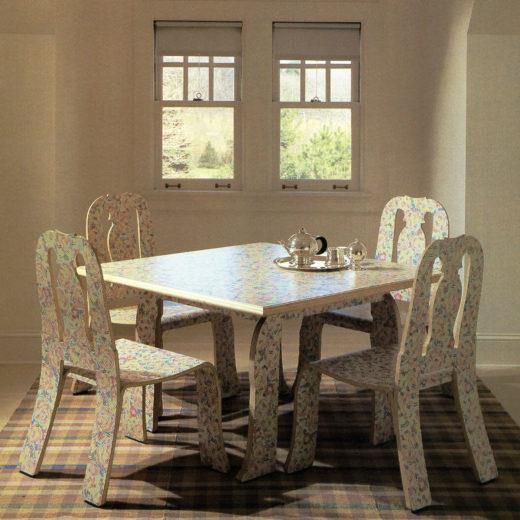

A chair is a mass-manufactured piece of furniture that exists as a component of layouts and rooms. You engage it with little thought, and it negotiates a certain physical, spatial, and hierarchical relationship that you subconsciously consent to with little risk; A Chippendale chair is a specific species of furniture with its own pedigree and history. If you know of it and recognize it, you acknowledge its cultural significance without necessarily being knowledgeable about it. It can be sentimental and reminiscent of people and places of a specific era. Still, you sit on it, all be it more aware that the chair is telling you how to behave around it; A Chippendale chair designed by Robert Venturi is an avant-garde interpretation of a chair that, to the uninformed might as well be modern art since one becomes extremely conscious that the object is designed and positioned in space very specifically. You do not carry the same nonchalance when you approach it for this chair in a living room carries the same pretense as a piece of artwork in a gallery: DO NOT TOUCH ME! (or in this case: do not sit on me!)

Robert Venturi’s Chippendale Chair is part of a collection of furniture manufactured and sold by Knoll in the mid-1980s as a collaboration between the technologically advanced furniture conglomerate and intellectually forward postmodern architect. The collection is an accessible means of owning manifestations of Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown’s ideas at a relatively affordable price. Its monetary inflation and cultural cachet are fundamentally attributed to the wide acceptance and topicality of the architects’ increasing popularity in a society that begins to overvalue the self-celebration of individual eclecticism, a zeitgeist that Venturi and Scott-Brown were interested in rationalizing. The singular object of the chair is less significant when compared to the theoretical injunctions the design represents. So, to understand the Chippendale Chair’s complex commingling of intentions, this object lesson will disentangle the object from its multiplicities and reconstruct it as a collage of semi-autonomous identities that each have their own agendas and stakeholders.

Three positions one might take (although by no means is that the limit) when interacting with Venturi’s Chippendale Chair are firstly, a piece of furniture with a designated function and history; secondly, as theory-practice that takes the form of a chair; thirdly, a piece of ‘high art’ that commoditizes fame by alienating the object from its context and function.

A Chair

We begin with a more literal, yet otherwise more pragmatic, lens in viewing Venturi’s chair. In an interview with Knoll, Venturi mentions that he “has a hobby about chairs”, suggesting that there is an awareness to typological variations in his collection and that by “connecting each chair with historic styles”[1], he is exploiting the audience’s knowledge and redeploying them to enrich the legitimacy and substance of his work. In Venturi’s own words, “the use of conventional elements in ordinary architecture evokes associations from past experience. Such elements may be carefully chosen or thoughtfully adapted from existing vocabularies or standard catalogs rather than uniquely created via original data and artistic intuition.”[2] It is therefore inescapable that this chair needs to be assessed as what it fundamentally is, a chair that is recognizable in the public consciousness. As a piece of furniture that is generally meant to be sat on, Chippendale chairs, as a broader species, have typological and stylistic traits that then break into sub-sects that differ by region or craftsman. Although it is uncertain whether it was a creation of Thomas Chippendale or it predates his school, the consensus is that the ribbon-back chair from England evolved into the classic Chippendale chair at around 1754.[3] Although initially modest, the second generation of models became more embellished with molding or fretwork in an attempt to become popular through novelty at the expense of taste. It was only after Chippendale’s position became secured, that the school ventured to be simple and refined. [4] It could be said that the classical Chippendale evokes a sensation of the classic, to articulate forms of nature hyperbolized to capture the fascination of public imagination. They also signified a return to a period of workmanship, where the organic color inconsistencies of natural wood came back into vogue[5] in stark contrast to the unity of modern mass production. An appetite for the tasteless excess that Adolf Loos critiques and a position Venturi himself leverages to bring about postmodernism. Nonetheless, it is clear that the original Chippendale targets society at large, if not only the aristocracy who have nurtured the sensibility for furniture that had aesthetic ambitions. It’s relationship to the human body is therefore subservient and infrastructural, meaning that the human mind perceives control over its relationship with the chair. Each chair, although adorned differently, is hierarchically equal in relation to another for they perform the same function and interact with one another in changing configurations of furniture and space. They exist as a homogenous collective and are substantially bland by nature. Comparing the archetype to Venturi’s rendition, although it is clear that he is appropriating a design for the masses, his choices in abstraction and flattening make it unfamiliarly familiar. Its primary function is not to be a chair, but instead be a representation or caricature of one. It alludes to the rich history in design development but ironically lacks the practical ergonomics attributed to the implied performance of a Chippendale chair. To someone who is engaging the object at face value, it is possible to perceive Venturi’s Chippendale’s Chair as not only inferior, but a failure when compared to the original, for not only is it less pragmatic or functional, whilst also being disproportionately uneconomical.

A Theory

So, if we are not to understand the chair as a chair, would it be more practical to approach it as a vessel that Venturi’s theoretical discourse inhabits? There is a reciprocal relationship between Chippendale chairs and Venturi’s work in Learning from Las Vegas for they fundamentally share the same theoretical underpinnings. As mentioned, although all of Venturi’s chairs rely on historic associations, they are “a stylization of a historical period” for he and Scott-Brown believed that “the expression of style and the symbol was a ‘sign’ and that there was no ambiguity”. In true Venturi fashion, the “style” he speaks of is to turn the image of the chair into “a sign, making it flat like a billboard, like a drawing”.[6] It is therefore evident that Venturi is less concerned about the object’s capacity to behave as a chair, but instead the program of a Chippendale chair is overhauled in favor for social critique. He redefines the relationship between the chair and the human body from being purely physical to visual and intellectual. This new dynamic leverages the sign having “denotative meaning in the explicit message of its letters and words”[7], which reflects “aesthetic ideals of today being one of richness over unity”.[8] But that said, the chair is not only denotative, but also connotative in expression, for in the same way it is heraldic in geometry, it is equally physiognomic in the reinvention of a bold silhouette and color. [9]

As mentioned, the relationship between Venturi and the Chippendale chair is reciprocal, for if Venturi brings in denotation, the chair provides physiognomic derivatives (such as size, texture, color, and recognition) for him to act upon. The reason Venturi chose the Chippendale chair, and indeed the reason it became the most fulfilled as a design, is because as an symbol or ornament, “it is dependent on explicit associations; it looks like what it is not because of what it is but also because of what it reminds you of.”[10] Venturi chose to make furniture because “these elements act as symbols as well as expressive architectural abstractions. They are not merely ordinary but represent ordinariness symbolically and stylistically; they are enriching as well, because they add a layer of literary meaning.”[11] They offer an accessible entry for audiences who disengage with the grandeur of architecture and forces them to tackle and digest the architect’s ideologies at the domestic scale, an unavoidable “communication over space”. [12]

A Metaphor

To own is to know. To own a piece of Venturi’s furniture is to say that you understand the coming of postmodernism, and that you are a stakeholder in the intellectual discourse that defines society. The commoditization of intellectual property allows for the exclusive right to participate in phenomena, hence inflating the value of objects. Venturi’s Chippendale Chair is one of the numerous designs that engage with its context too intently, to the point that it removes itself form its context, hence becoming anti-functional. Like any good public speaker or politician, Venturi’s chair is highly receptive and humorously responsive to its audience. The metropolitan society that resulted from the mechanization of modernity and capitalism is often diagnosed as ‘ill’, whilst its inhabitants live “in a homogenous, flat grey color with no one of them being preferred to another”. [13] The society of mass production is concerned the monetary “exchange value which reduces all quality and individuality to a purely quantitative level”[14] and “the exactness and the minute precision of the form of life” that “coalesced into a structure of the highest impersonality.” [15] Society at large was unknowingly and unwilling objectified into a quantitative field of moving parts that are valued upon their function only. In retaliation, the individual turned towards a subversion of conventional taste for the sake of “being different – of making oneself noticeable”. [16] Venturi was definitely aware of the increasing preference of diversity over unity, for he notes that “expression has become dry, empty and boring – and in the end irresponsible” in “rejecting explicit symbolism and frivolous applique ornament”[17] and that the declaration of identity can be achieved “through the connotation of implicit in the physiognomy of pure architectural form”. [18] In a way, Venturi’s chair was designed to personify the metropolitan who yearns for individuality, to intentionally objectify one’s projection of oneself to alienate oneself from the norm. Its very existence as a pure metaphor of what is wrong with metropolitan life and a solution towards a new zeitgeist invigorated the imagination of intellectuals, hence inflating its perceived value as not just a chair that is a product of modernity’s manufacturing framework, but an artifact that synthesized a moment in time.

As such, Venturi’s chair, as a design, has transcended its domestic context, and therefore has become anti-functional. Society’s collective agreement is that the object should no longer behave as a chair, but as an exhibit in museums, as evidence in archival timelines. However, I would argue that doing so actually detracts from the object by muting its ability to speak. Venturi designed his chair to exist in the domestic sphere, to engage in conversation with people in distinctly different homes, to be viewed and appreciated in a variety of configurations to express the universal need for changes to modernity. It is counterintuitive to put this design into an absolutist space, a museum where the contextual variables are fixed and singular. It is equally counterintuitive to take a piece of furniture that is designed to stand out subtly and put it in a room with other artifacts that are also quirky and noisy, thereby drowning its voice, its message. When discussing how we ‘see’, John Berger notes that when art is reproduced and each is “seen in a different context”, “its meaning is diversified in its travels”[19]. It is less important that we see the ‘original’ prototype physically in a convenient space, but that we experience it the way Venturi intended us to.

So what now?

As it stands, Venturi’s Chippendale Chair is a piece of cultural artifact. It is art, not a chair. Its program is not to contend with utilitas, firmitas, and venustas, but to shout for attention in an endless catalogue of other loudspeakers on the behest of Venturi. But this chair is only a piece of Venturi’s collaboration collection, and this collection is only part of an ongoing series of novelty productions theorist and designers use to attain authority by ‘publishing’ their theoretical conjectures as tastemakers. It is not that I am saying this is problematic, but it is important we the consumers, as well as the designers and manufacturers, acknowledge that we are operating with a different set of intentions. So when Virgil Abloh drops a limited collection with IKEA that you have to queue outside the store overnight for, we acknowledge that we are not standing in line for furniture, but we are bidding to be part of a design movement generated by his pathos, and once his $99 carpet that looks like a receipt ends up on our living room floor, we will consciously tip-toe around it with a self-eluded sense of reverence and caution.

[1] Knoll. “The Venturi Collection”, 2018, https://www.knoll.com/story/shop/robert-venturi-q-a

[2] Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. “Learning from Las Vegas”, The MIT Press, 1977, 129.

[3] Herbert Cescinsky. “Chippendale’s Ribbon-Back Chairs” in The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol 37, Oct 1920, 195.

[4] Cescinsky. “Chippendale’s Ribbon-Back Chairs”, 196.

[5] Harper’s Bazaar. “Seat for Chippendale or Sheraton Chair”, 28 Apr 1883, 260.

[6] Knoll. “The Venturi Collection”

[7] Venturi, Scott-Brown. “Learning from Las Vegas”, 100.

[8] Knoll. “The Venturi Collection”

[9] Venturi, Scott-Brown. “Learning from Las Vegas”, 101.

[10] Venturi, Scott-Brown. “Learning from Las Vegas”, 93.

[11] Venturi, Scott-Brown. “Learning from Las Vegas”, 130.

[12] Venturi, Scott Brown. “Learning from Las Vegas”, 8.

[13] George Simmel. “The Metropolis and Mental Life” in “On Individuality and Social Forms”, University of Chicago Printing Press, 1971, 14.

[14] Simmel. “The Metropolis and Mental Life”, 12.

[15] Simmel. “The Metropolis and Mental Life”, 14.

[16] Simmel. “The Metropolis and Mental Life”, 18.

[17] Venturi, Scott-Brown. “Learning from Las Vegas”, 103.

[18] Venturi, Scott-Brown. “Learning from Las Vegas”, 100.

[19] John Berger. “Ways of Seeing”, Penguin Press, 1972, 20.

notes:

This was originally produced as an Object Lesson for ARC242 at Syracuse University, spring 2020.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. Penguin Press, 1972.

Cescinsky, Herbert. Chippendale’s Ribbon-Back Chairs. In The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol 37, No. 211, Oct 1920.

Simmel, George. The Metropolis and Mental Life. In On Individuality and Social Forms, University of Chicago Printing Press, 1971.

Harper’s Bazaar. Seat for the Chippendale or Sheraton Chair. In Harper’s Bazaar, Vol 16, Issue 17.

Knoll International. The Venturi Collection. In Design Pulse. https://www.knoll.com/story/shop/robert-venturi-q-a

Venturi, Robert and Denise Scott-Brown and Steven Izenour. Learning from Las Vegas. The MIT Press, 1977.

This was originally produced as an Object Lesson for ARC242 at Syracuse University, spring 2020.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. Penguin Press, 1972.

Cescinsky, Herbert. Chippendale’s Ribbon-Back Chairs. In The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol 37, No. 211, Oct 1920.

Simmel, George. The Metropolis and Mental Life. In On Individuality and Social Forms, University of Chicago Printing Press, 1971.

Harper’s Bazaar. Seat for the Chippendale or Sheraton Chair. In Harper’s Bazaar, Vol 16, Issue 17.

Knoll International. The Venturi Collection. In Design Pulse. https://www.knoll.com/story/shop/robert-venturi-q-a

Venturi, Robert and Denise Scott-Brown and Steven Izenour. Learning from Las Vegas. The MIT Press, 1977.