Memo 004

Parley on Provoking, Process, and Postmodernism

Nicholas Chung, featuring Zicheng (Roy) Zhang, 16 July 2023

A late-night conversation between Nic and Roy, our chat unfolds around the much-debated topic of architects’ social responsibility and its limit of bringing about meaningful changes. We touched on the disparage between architectural theory and practice and went on an extensive tangent on Stern’s The Doubles of Post-Modern. We also introduced our work methodology and how our own works engages our them with the larger sociopolitical contexts.

Nic: Why is it important to develop design arguments? Especially in professional practices where it’s all about pragmatic resolution rather than the pure execution of concepts.

Roy: Well, I think that really stems from the great disparity between practice and theory in our field.

Nic: I remembered you were talking about (Aldo) Rossi on a similar point –

Roy: Yes, I was reading Rossi’s Architecture for Museums where he makes an argument for architectural theory. He believed the highest measure for the architects is to make monuments for the “museums” for they are “final signs of a more complex reality”. In his view, design theory should be the driving force of any architectural education – how to create comes after how to theorize, so to speak.

Nic: So, should we make a distinction between theory and argument (or position)? Because you can construct an argument without being theoretical.

Roy: That’s fair.

Nic: You don’t really need to get philosophical for something to be meaningful, but I think you do need a rationale for your work to have impact.

Roy: Yeah but, uh – (flipping pages of notes in silence) I’m trying to find that quote I like -

(more silence)

Roy: uh no. There’s nothing I like of Rossi’s elusive writing. What was it you were saying again?

Nic: In terms of how we, the two of us, work, I guess the question is why do we approach design in such different ways? Because when I design, it feels like constructing a debate or legal argument where you have the claims, the plaintiffs, the defendants, and the evidence. Whereas you make sequential arguments as to why your version of reality that you’re proposing is the most plausible and compelling.

Roy: Well, almost always there’s a problem to solve. Architectural practice is about problem solving, so if there’s a problem there’s a need for a solution.

Nic: But more often than not I feel like we create problems to solve rather than find problems to solve, does that make sense?

Roy: Yeah, and that’s the difference between a theoretical project and architectural practices. Practices deal with “realistic” or “pragmatic problems” (hand gestured air quotes), whereas architecture theory deals with “first world” or “existential” problems that are out of the realm of any pragmatism.

Nic: Okay, I don’t agree that it is unrealistic, because I think the energy crisis, displacement etc. are issues that are real but are simply too ambitious for individual projects to contend with.

Roy: No, I think problems of energy consumption and gentrification are definitely issues architectural PRACTICE can contend with. It’s the existential questions theoreticians post that seemed to be far out of the realm of what architecture practices can grapple with. I was reading Koolhaas’s “Preservation is Overtaking Us” for my thesis where he argues something along the lines of: preservation is overtaking us in a reality that the past is becoming increasingly current, and when the past eventually overtakes the present, what architects are preserving now is actually the future, which are just existential bullshit.

Nic: Right and that’s my problem with Koolhaas’s writings because what he says is definitely impactful, but I don’t know what to do with it.

Roy: Right? And that’s theory, that’s why Eisenman is such an important figure – I was reading on him recently – Robert Stern argues that there is two sides to postmodernism, schismatic and traditional postmodernism. Schismatic represent a clear break from Western humanist culture, and that’s Eisenman. And then you have traditional postmodernism, which is basically Venturi, Moore, Graves, and everyone else. So traditional postmodernism is about moving away from the so-called “modern style” – where architecture needs to take on social responsibilities and communicate with the masses, not just private clients who can appreciate the pristine whiteness in their upper class boubles – so that’s one kind of postmodernism that returns to the humanist traditions. Whereas schismatic postmodernism, which Stern attributed solely to Eisenman, argues that the modern style needs to move even further beyond Western humanist culture and that architecture is just architecture, cutting itself lose from even the fundamentals of program and space. It’s all about pure form, because the old reconciliation between form and program has gotten so out of – it just can’t be reconciled anymore. But architecture needs to remove itself from all the social connotation and thus is all about compositional delight.

Nic: So basically, it’s a difference in attitude. What should the designer be engaging? So where do you stand in this?

Roy: Sigh – that’s hard… (eye roll)

Nic: I mean it’s an attitude question – right now do you think architects today are stretching themselves too thin? Are we trying to deal with too many things at the same time. It’s something incredibly prevalent especially with the Biennale – it feels like we are not doing architecture (?) or not producing architectural arguments for things that architecture design can solve, and I think that there’s a case to be made for the schismatic approach – the regression away from the role of cultural curator.

Roy: Yeah… It’s been thoroughly talked about that architecture as a profession has a limit to what we can do. I think the latest biennale is just a testament to no matter how hard we try to care, there’s only so much we can do within the realm of architecture, and all other efforts are just… I don’t know… they’re art projects under the disguise of “architecture”.

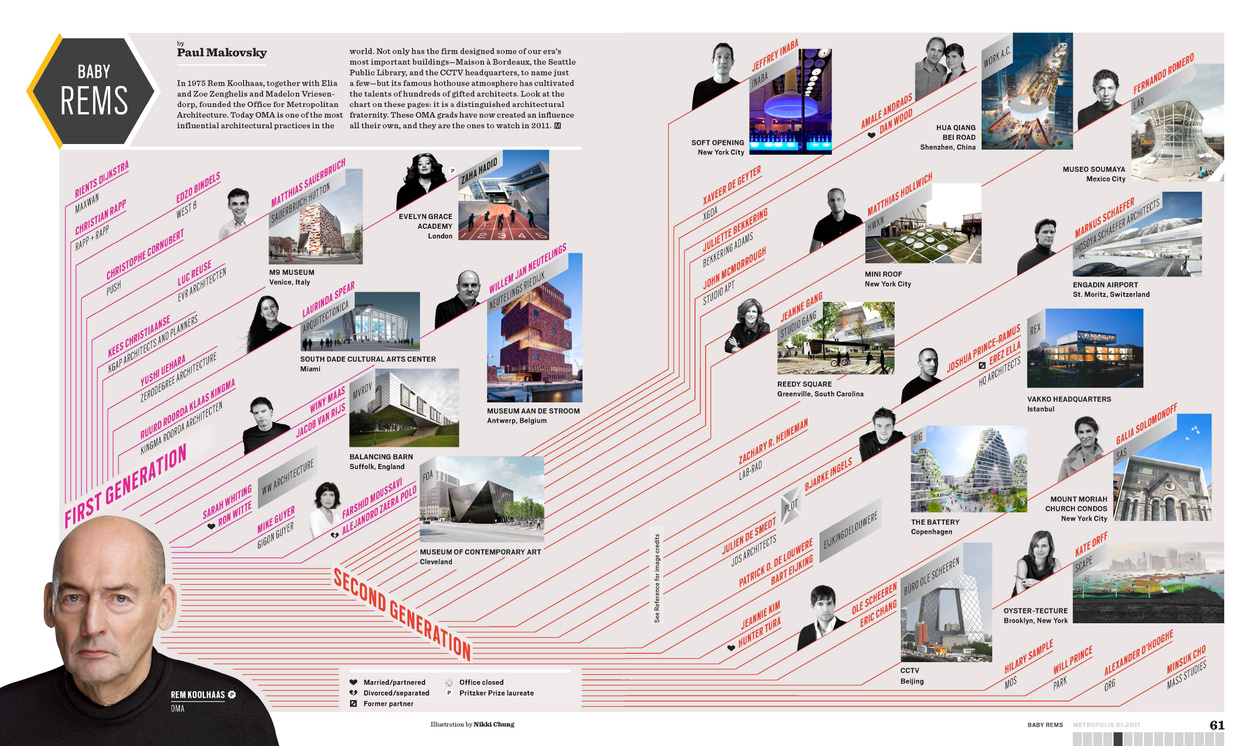

Nic: In a way we risk devaluing our work, or our social capital by engaging with issues that we are uninformed in and are impossible for us to solve. Everyone wants to be a “Baby Rem”, and we are currently too preoccupied in being “influencers” or “tastemaker”. It feels like we are becoming content in just sounding the alarm instead of actually trying to solve the problem.

"Baby Rems" Makovsky and Chung

"Baby Rems" Makovsky and ChungIntermission

Nic: So we veered quite far into postmodernism, and that can be it’s own memo later, however I wanted to ask you: what type of arguments should we be making as architects? Or more specifically what type of arguments should our designs be making? And I’d like you to draw a distinction between the work we produce as students and the projects we participated in during practice.

Roy: Oh that would be a perfect diagram! Do you remember the diagram (Britt) Eversole showed us of the avant-garde artists, educators, and practitioners – I think there are different roles for different architects –

Nic: Yeah but the follow up would be how you would construct the argument? Maybe let’s talk about it in context of our own work – so as a student the past five years, how did you construct design arguments or positions?

Roy: I mean there’s only one time I constructed my own argument and that’s my thesis, but my thesis isn’t really a design project…

Nic: Maybe let’s change the scope first to a studio project – your third-year project in Eversole’s studio “COOP”. It was a very pragmatic setup, you were working with Elizabeth Warren’s housing fund and yes though there was the Koolhaasian-scale, lofty issues of housing and inequity in America, those were not conditions that you fabricated or exaggerated. So I was wondering how did you and Kiley (Russell) simulate the architectural strategy playing out in your heads before committing to the form you ended up with?

Roy: Uh I mean the whole Warren policy was brought to our attention by Eversole honestly, and he said “I always wished someone could make an architecture proposal to make it work”. That might be somewhat disappointing but that’s how the idea came to us .

Nic: But it is very on par with disciplinary history, I’m thinking about Hugh Ferris’s drawings in Metropolis of Tomorrow because when the setback zoning laws came out in 1916, no one could conceptualize what that means physically. So the massings and visions he drew underpinned the New York look we see today. What you did is very much in that tradition. I’m going to probe you a bit more on the COOP project – how did you guys develop the system? The system of the module and then how people sign themselves up as part of the Warren policy package – because it is very sequential and you’re making narrative points of how people will live out their lives in this framework.

Roy: It really came from research. We were looking at how people get their housing, and uh.., it’s really a traditional way of finding a problem, and then coming up with a solution.

Nic: Was it finding the problem or defining the problem?

Roy: It’s defining, I think it’s defining. Yeah, it was defining the problem and then coming up with a solution because the problem with Mattapan was uh… I forgot what the problem was (chuckles) oh that’s must sound very bad –

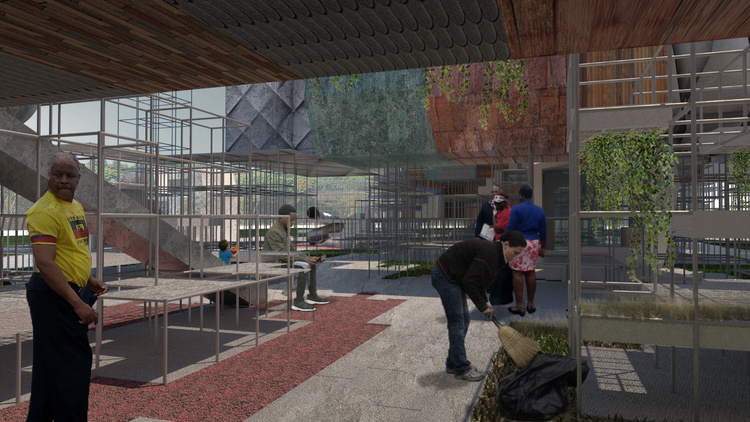

Nic: I’m not sure if this will help jog any memories but I remember you guys were looking at Mattapan and Milton, and the contrast between the quality of life between them. And what really struck me about your final presentation was that you guys almost did it like a real estate pitch, the deck you guys presented was filled with these idealistic renders of white middle class families in suburbia but the drawings you showed on the boards are of African-Americans, immigrants and the real people who live in Mattapan, as well as renders of how they would probably activate the architecture. I thought that was really profound but I don’t know if that was useful in remembering the problem of Mattapan from research.

Render from presentation slides

Render from presentation slides Render on Conceptboard

Render on ConceptboardRoy: There was not enough housing and there were a lot of problems with government subsidies. They subsidize developers and a wide range of government agencies like the FHA. Developers will build affordable housing alongside commercial housing for tax benefits. The government subsidies also go to banks and housing agencies with loans and lotteries. But after we looked into it, they were all very low in efficiency, and they are very unstable because they depend heavily on government funding. And the residents could only get money from those intermediary agencies instead of the government directly and Elizabeth Warren’s proposal was here to solve that, to get rid of that layer of bureaucracy and get the money directly to residents so they can put it to their own housing circumstances, and that’s where the idea of setting up a non-profit agency as part of the design project came to be. The architecture system works with government policy. People have their grant money, and as planners, we thought we could use our expertise to develop an architectural system that can mass produce these modular units. People can use the money they get from the government and invest in this NPO and we give them a house, as cheap as possible. Our proposal bridged the gap between circumstance (residents getting money directly from the government under Warren’s proposal) and desired result (home ownership).

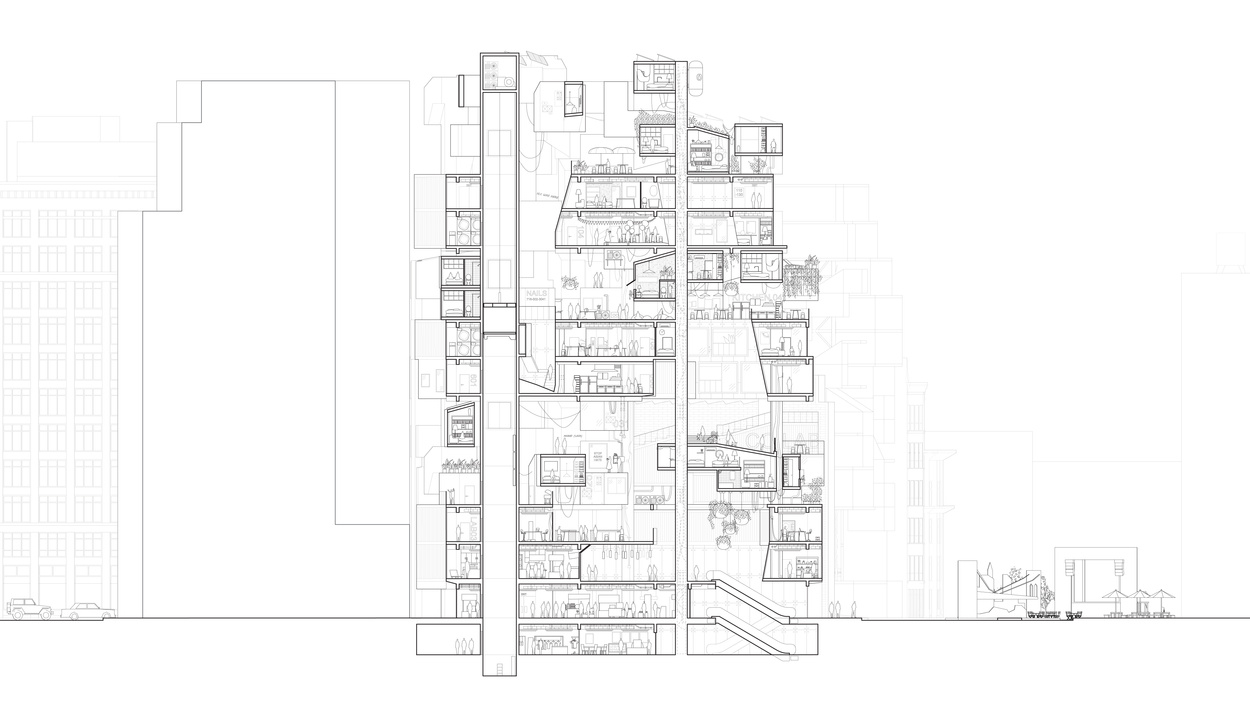

Nic: That’s fascinating, because we never actually had a conversation about this facet of your project. So you guys designed the architectural parts for residents who now have access to funding to do something with it. Now that you put it that way, I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the project Angelina (Zhang) and I did called “SoHo Commoning” because it operated in almost the exact opposite way you did COOP and what you were criticizing before. The circumstances were similar in that there was a policy agenda of upzoning SoHo with clear legal implications. Though admittedly we ended up playing very fast and loose with zoning setback laws, the project is a riff on the Community Land Trust framework already in play in parts of New York like Astor Place. The framework is that when you buy or rent, it does not come with a deed covenant, meaning the NPO collective owns the management rights of all land whereas you own the right to use. It stemmed from a naive desire to solve everything(?) So we were interested in Right to the City, right to civic life, economic mobility, the disappearance of craft culture, etc. etc. etc. And we crammed all of that under the notion that New York is suffering from a homelessness issue, because of high rent, inequity etc. However, we argue that is fundamentally different from house-less-ness. People in the city aren’t just needing a roof over their heads, they’re missing the sense of safety and support you find from home, from community. And that became the problem we created to solve through the design project. The incentive was when you move in you get your apartment module as well as a production space in the market commons. So it also plays to the historic culture of SoHo, and you hit those buzzer works of resiliency and community building. In a way it was never about the building, it was always about the conceptual framework that can birth this kind of architecture.

Narrative section from SoHo Commoning

Narrative section from SoHo CommoningRoy: So do they pay rent?

Nic: We did a proforma and it’s like 50% commercial, 30% rental, and then 20% affordable, the math checked out.

Roy: That’s very New York City (laugh)

Nic: It’s a zoning requirement… But the product was in very stark contrast to CO-OP, because we were creating a problem to solve, and you guys were defining a problem.

Roy: But what does that mean? What’s your problem? It’s not homelessness, right?

Nic: No, it wasn’t, because there was just too many things to work with being in New York City but it wasn’t like in your case where there was a clear gap and question mark for you guys to respond to. But in the SoHo project, there was a sea of circumstances and we were trying to aggregate and mold them into a problem – so it was like creating a villain that is so obviously problematic that our design was both justifiable and desirable.

Roy: That feels like reach.

Nic: Yeah that project I feel like falls into a common fallacy in design school where we design non-existent problems instead of design solutions, which is what I was trying to hint at in the beginning of this conversation.

Roy: Ah~

Nic: Yeah and I think that’s why I really enjoyed COOP as a project because it engaged creatively real world circumstances but it didn’t force itself into a proposition.

Roy: Well it is definitely a proposition, but it’s –

Nic: But it didn’t force itself into it.

Roy: Yeah it’s a solution pretty much. It’s not a proposal to a fabricated problem.

Nic: Yep, I’m going to close with this point because you mentioned your project came out of research, and the contrast between my preference of finding a problem and your preference in defining an existing problem is really evident in the way we conduct research.

(silence)

Roy: hm….

Nic: So in my case the way I formulate an argument is to have a sexy thesis and then cherry pick the evidence that fits it so the narrative becomes self-contained but fool-proof. For me it worked very well because it was a very efficient way of establishing compelling narratives or worldviews that captured people’s attention. But in your case you do it very differently.

Roy: Yeah because your arguments are developed in anticipation of them being attacked, hence the constant searching for evidence that supports it.

Nic: Whereas you read everything before you commit to an opinion. You’re interested in the relationship between different thinkers and their arguments. You need to know everything there is to know first and then you’re comfortable to position yourself amongst this field of scholarship.

Roy: Yeah because otherwise I don’t know where to start…

Nic: But why is that?

Roy: I don’t know, it’s just how I work. I’ve been thinking when I was travelling with my dad, and was reflecting on my thesis year. What does it mean when everyone says I’m the “history” guy, I’m “historical” – what does that even mean? It’s not like I’m particularly interested in reading history, I’m not well versed in WWII or anything like that. Or I really don’t get caught up in big names – actually I do get caught up in big names. I do like looking at those. But what does it mean to be “historical”? Then I figured out that I look at things from the perspective of history. When I look at postmodernism, I don’t look at it as an argument with multiple threads that can be extracted in order to support my own case. I need to understand its lineage. I need to understand what came before it, what came after it, and what then was before modernism. I need to understand the lineage and try to position myself. And that’s exactly how I developed my thesis “Adaptive Misuse”, because I didn’t have my thesis before understanding what adaptive reuse is, what historical preservation is, because the term Adaptive Misuse is something I declare as the next phase of adaptive reuse. So positioning my thinking in a historical timeline, and try to think what came before it and where it is going. I think that’s why people say I’m historical - that’s how I think. I see things in a lineage of multiple historical events and knowledge.

Nic: Because if you work outside of that lineage it becomes fantasy not reality.

Roy: It’s reality but –

Nic: It’s a version of reality that’s further and further away from the real.

Roy: Yeah it’s unsubstantiated. There are pieces here and there that support your argument like in your thesis (Shinjuku Flaneuring) you have Gridnr Urbanism, Made In Tokyo etc. Or Placeless Places where you find a problem which is the diminishing of third spaces, and then you find a sea of articles from which you extract useful excerpts to support your idea or solution. So it isn’t necessary for you to have a timeline. You have a timeline but the lineage of those thoughts are not –

Nic: It’s irrelevant. They’re referential but irrelevant.

Roy: Yeah exactly. But for me, for Adaptive Misuse – to understand postmodernism I need to understand modernism, to understand modernism I need to go back to the renaissance.

Nic: And then you need to understand how the mannerists relate to the baroque etc. etc. etc.

Roy: Yeah and how they treat history differently. And to me that lineage is also important. I don’t know I think that somehow gives my project validity.

Nic: Because it justifies its existence, which is the whole point of having a position – to sustain the argument that the work is irrelevant, and we should care. The fact that you go to such lengths to root it in factual reality gives your work a lot of cachet. This is also why I thought your project with Wendy (Li), the 99:1 superblock, feels detached from your repertoire. I love the project but unlike a lot of your other projects, it takes a moral value statement and pushes it to the extreme.

Roy: Yeah and I never go to the extreme (chuckle) As Eversole pointed out in my thesis review. I said I was oscillating between how much is too much. I was oscillating between being deconstructivist/purely formal and being too preservationist where you don’t see the changes. So that’s why the project got a bit stuck, because I was constantly moving back and forth between those lines. And Eversole’s comment was “I’m surprised you even contemplated between those lines instead of just going maximalism with everything.”

Nic: But that’s also a very Eversole thing to say, he’s all about doing a physical model again but bigger. But I also agree with him though. Because when a critical audience sees something, it’s in their nature to strip it down. That’s also true in practice. If you show up with a vision at 100%, the client will introduce budget constraints or cost overruns that will leave your project at 60% by the end of it. But if you rock up at 200%, the project will probably end up closer to 100%.

Roy: Yeah, exactly.

Nic: And that’s the big discrepancy I was trying to tease out at the beginning – the difference between having an argumentative position in practice versus having one in academia. The realism versus maximalist.

Roy: Yeah, because there is an inherent pragmatism in architecture that artists ignore. That’s why Eisenman was so inspiring in a sense because he transcends the line between architects and artists. He made livable sculpture.

Nic: Mhm.

Roy: His houses – those intersecting walls, self-referential and autonomous. They have pragmatism in them – as in you can live in them and there are windows and staircases. However, fundamentals of architecture, programs and the ease of space, are irrelevant in his “buildings” – they are manifestos, artifacts and proof-of-concepts that resonates with and appreciates nothing but their own beauty. That’s why I love his crazy houses because they are the ultimate manifestation of architecture as context. They are sculptures that decided last minute they want to be houses, pragmatism comes second, third – last! As a matter of fact…

Nic: Is being quirky more important than being pragmatic?

Roy: For an artist, yes.

Nic: And this obviously goes back to the Eversole diagram of the artist, the educator, and the practitioner.

Roy: Huh yeah, interesting.

"Contemporary Model of the Architectural Avant-Grade" Britt Eversole

"Contemporary Model of the Architectural Avant-Grade" Britt Eversole

notes:

featured on PART6

Roy Zhang is an M.Arch II candidate at Yale SOA. He completed his B.Arch at Syracuse University (Summa Cum Laude) with a keen interest in architectural theories, research and design. His approach and process privilage attentiveness to rigorous site analysis and social dynamics. Roy’s work has been exhibited as part of “Cultivated Imaginaries: Superblock and the idea of the city” with Liang Wang at Syracuse University and “Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America” with Studio SUMO at the Musuem of Modern Art.

featured on PART6

Roy Zhang is an M.Arch II candidate at Yale SOA. He completed his B.Arch at Syracuse University (Summa Cum Laude) with a keen interest in architectural theories, research and design. His approach and process privilage attentiveness to rigorous site analysis and social dynamics. Roy’s work has been exhibited as part of “Cultivated Imaginaries: Superblock and the idea of the city” with Liang Wang at Syracuse University and “Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America” with Studio SUMO at the Musuem of Modern Art.